When a pharmacist hands you a pill bottle with a different name than what your doctor wrote, you might wonder: Is this the same drug? Is it safe? The answer isn’t as simple as it seems. Behind every generic substitution is a web of medical society guidelines, regulatory standards, and specialty-specific concerns that shape how doctors prescribe and how patients get treated.

Why Generic Drugs Are Everywhere - And Why Some Doctors Worry

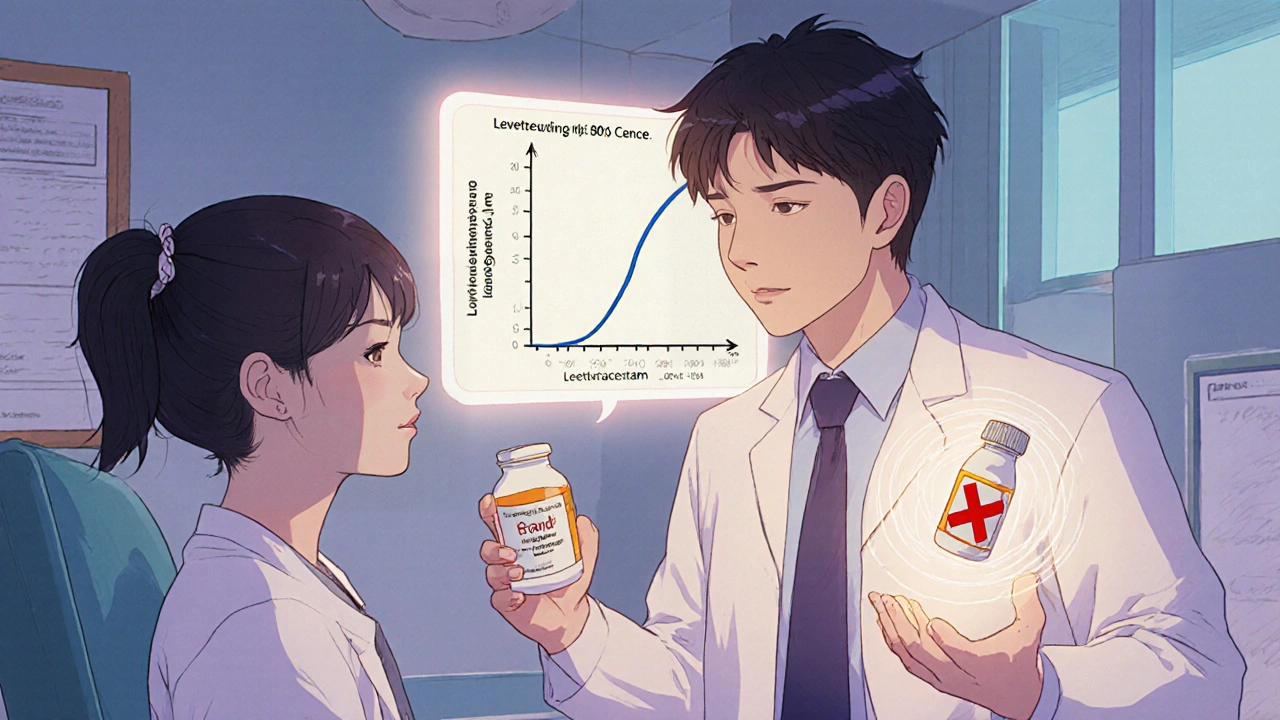

Generic drugs make up 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S., but they account for just 23% of total drug spending. That’s not just a win for insurance companies - it’s a win for patients who need long-term medications. The FDA approves generics based on strict bioequivalence rules: they must have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand-name version. They also must show they’re absorbed into the bloodstream at the same rate and to the same extent - within an 80% to 125% confidence interval. But here’s the catch: that range isn’t zero. For most drugs, it doesn’t matter. A patient taking a generic statin for cholesterol won’t notice a difference. But for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index (NTI), even small changes in blood levels can mean the difference between control and crisis. That’s where medical societies step in.Neurology: The Case Against Substituting Anticonvulsants

The American Academy of Neurology (AAN) has one of the clearest and most firm stances: do not substitute generic anticonvulsants. Why? Because seizures don’t wait. A 10% drop in blood concentration of a drug like levetiracetam or phenytoin might not seem like much - but for someone with epilepsy, it could trigger a breakthrough seizure. The AAN’s position isn’t based on fear. It’s backed by clinical reports. One survey of neurologists found that 68% believed generic substitutions had led to treatment complications in their patients. These aren’t anecdotes - they’re patterns. The FDA’s bioequivalence range, while scientifically valid for most drugs, doesn’t account for the extreme sensitivity of the brain to small fluctuations in drug levels. For these patients, stability matters more than savings. Some states have responded by requiring prescriber consent before substituting NTI drugs. Others haven’t. That creates confusion for pharmacists and anxiety for patients who’ve been stable for years - only to get a different pill with the same name.Oncology: Off-Label Use and the NCCN Safety Net

In cancer care, the rules are different. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) doesn’t just accept generic drugs - it actively incorporates them into treatment guidelines, even for uses not originally approved by the FDA. That’s because many cancer drugs, once proven effective for one type of tumor, are used off-label for others. Generic versions of these drugs are often the only affordable option for patients needing long-term treatment. The NCCN Compendia is the only recognized source for Medicare coverage of off-label cancer drug uses. When a generic version of a drug like paclitaxel is listed in the NCCN guidelines for a new cancer type, insurers are required to cover it - even if the brand-name version was never approved for that use. This creates a unique system where generics aren’t just cost-savers - they’re enablers of access. Doctors in oncology don’t worry about bioequivalence the way neurologists do. Cancer drugs are often given in high doses with close monitoring. If a patient’s response changes after a switch, labs and imaging will catch it quickly. For them, the bigger issue is whether the drug is available at all - and generics make that possible.

The AMA and Drug Names: Safety Through Clarity

One of the most overlooked parts of the generic drug system is naming. The American Medical Association’s United States Adopted Names (USAN) Council doesn’t just assign names - it prevents confusion. Their job is to make sure that generic drug names don’t sound or look too similar to others. For example, if a new drug ends in “-pril,” you know it’s an ACE inhibitor. That’s intentional. The council avoids prefixes that might be mistaken for other drugs - like confusing “-zolam” with “-zepam.” A single misread name can lead to a dangerous error. That’s why the USAN Council spends years reviewing proposed names, checking them against thousands of existing drug names, and even testing them with pharmacists and nurses. This isn’t bureaucracy. It’s prevention. A study in the AMA Journal of Ethics showed that standardized naming reduces medication errors by up to 30% in high-risk settings like ICUs and emergency rooms. For patients on multiple drugs, especially seniors, this clarity can be life-saving.What the FDA Says vs. What Doctors Do

The FDA says generic drugs are therapeutically equivalent - and they’re right, for most cases. Their data shows substitution rates hit 90% when a generic is available. But that’s an average. It doesn’t tell you what’s happening in a neurologist’s office, a cancer clinic, or a psychiatric ward. Doctors don’t ignore FDA guidelines. They interpret them. A cardiologist might switch a patient from brand-name lisinopril to generic without a second thought. A psychiatrist might avoid switching an antipsychotic like clozapine because of the risk of relapse. A rheumatologist might stick with brand-name infliximab because biosimilars - while similar - aren’t always interchangeable in autoimmune diseases. The gap isn’t between science and practice. It’s between population-level data and individual patient needs. Medical societies exist to bridge that gap.

State Laws vs. Medical Guidelines: A Messy Reality

Here’s where things get complicated. State laws often force pharmacists to substitute generics unless the prescriber says “dispense as written.” But those laws don’t always align with what medical societies recommend. In some states, NTI drugs are protected - substitution requires explicit permission. In others, pharmacists can switch any generic, anytime. A patient in Texas might get a different version of their seizure medication than one in New York, even if they have the same doctor and same insurance. Pharmacists are caught in the middle. They’re trained to save money and increase access - but they’re also trained to prevent harm. When a guideline from the AAN conflicts with a state law, pharmacists often call the prescriber. That delays care. It frustrates patients. And it adds administrative burden to an already overworked system.What Patients Should Know

If you’re on a medication for epilepsy, bipolar disorder, warfarin, or certain immunosuppressants - ask your doctor if switching to a generic is safe. Don’t assume it’s fine just because it’s cheaper. For these drugs, consistency matters more than cost. For most other drugs - antibiotics, blood pressure meds, antidepressants - generics are safe, effective, and widely recommended. The FDA’s approval process works. But don’t let that make you complacent. If you feel different after a switch - worse, not better - tell your doctor. That’s not resistance. That’s advocacy.What’s Next for Generic Drug Guidelines

Medical societies are moving toward more alignment with the FDA’s therapeutic equivalence ratings. The Orange Book, which lists which generics are interchangeable, is becoming a reference point in more specialty guidelines. But exceptions will remain - and they should. The future isn’t about banning generics. It’s about smart substitution. It’s about recognizing that not all drugs are created equal in how the body handles them. It’s about letting science guide policy, not the other way around. For now, the best advice is simple: Know your drug. Know your condition. And if you’re on a drug where small changes can have big consequences - don’t let a pharmacy decision override your doctor’s judgment.Are generic drugs really as good as brand-name drugs?

For most medications, yes. The FDA requires generics to have the same active ingredient, strength, and bioequivalence as the brand version. Studies show they work just as well for conditions like high blood pressure, diabetes, and depression. But for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index - like anticonvulsants, warfarin, or certain immunosuppressants - even small differences in absorption can affect safety. In those cases, sticking with the same brand or generic version is often recommended.

Why do some doctors refuse to allow generic substitution?

Doctors who oppose substitution usually treat patients with conditions where tiny changes in drug levels can cause serious harm. Neurologists, for example, avoid switching anticonvulsants because a slight drop in blood concentration could trigger a seizure. Psychiatrists may avoid switching antipsychotics due to relapse risk. These aren’t blanket rejections - they’re targeted safety measures based on clinical experience and data.

Can I ask my pharmacist to give me the brand-name drug instead of a generic?

Yes. You can always request the brand-name version. However, your insurance may require you to pay more out of pocket, or even deny coverage unless your doctor writes "dispense as written" on the prescription. If cost is a barrier, talk to your doctor - they may be able to help you find a patient assistance program or switch to another medication that’s covered.

What does "NTI" mean, and why does it matter?

NTI stands for narrow therapeutic index. It means the difference between a safe, effective dose and a toxic or ineffective one is very small. Drugs like warfarin, lithium, phenytoin, and cyclosporine fall into this category. Even minor changes in how the body absorbs the drug can lead to dangerous side effects or treatment failure. That’s why many medical societies recommend avoiding substitutions for NTI drugs unless absolutely necessary.

Do generic drugs have different side effects?

The active ingredient is the same, so the core side effects should be identical. But generics can have different inactive ingredients - like fillers, dyes, or coatings. Rarely, these can cause allergic reactions or affect how the drug is absorbed. If you notice new side effects after switching to a generic, report them to your doctor. It’s not common, but it happens.

How do I know if my drug is considered NTI?

Ask your doctor or pharmacist. Common NTI drugs include anticonvulsants (phenytoin, carbamazepine), blood thinners (warfarin), thyroid meds (levothyroxine), and immunosuppressants (cyclosporine, tacrolimus). The FDA’s Orange Book also labels some drugs as NTI. If you’re unsure, check the drug’s prescribing information or look up the drug class - drugs with tight dosing requirements are usually flagged.

Posts Comments

Gus Fosarolli November 29, 2025 AT 00:04

So let me get this straight - the FDA says generics are fine, but neurologists are out here treating patients like they’re walking nuclear reactors? 🤔

Meanwhile, my pharmacist swaps my blood pressure med like it’s a game of musical pills and I’m just supposed to nod and smile. Guess I’ll keep my seizures and my savings separate, thanks.

Evelyn Shaller-Auslander November 30, 2025 AT 04:19

i had a seizure last year after they switched my generic keppra… no one warned me. now i only take the brand. worth every penny. my brain is not a budget experiment.

Asbury (Ash) Taylor November 30, 2025 AT 13:58

The precision with which medical societies articulate risk profiles for narrow therapeutic index drugs is a testament to the rigor of clinical governance. While cost containment is a laudable societal goal, patient safety must remain the non-negotiable cornerstone of pharmacotherapy. The divergence between regulatory thresholds and individualized physiological response underscores the necessity of physician discretion in substitution protocols.

Kenneth Lewis December 2, 2025 AT 03:35

generic drugs are fine until you start feeling like a zombie or your seizures come back… then you’re like… wait, did i just get ripped off? 😑

also why do pharmacists always act like they’re doing you a favor? just give me what my doc ordered.

Jim Daly December 3, 2025 AT 03:54

THE GOVERNMENT IS MAKING US TAKE FAKE MEDS!!

THEY WANT YOU WEAK!!

THEY DON'T WANT YOU HEALTHY!!

THEY WANT YOU DEPENDENT!!

THEY'RE WORKING WITH BIG PHARMA!!

IT'S A CONSPIRACY!!

THEY PUT LYE IN THE GENERIC LITHIUM!!

Tionne Myles-Smith December 4, 2025 AT 10:26

My dad’s on warfarin and they switched his generic and he nearly had a stroke. We called the doctor, they switched him back. Now we have a note on his file that says NO SUBSTITUTIONS. If you’re on anything that keeps you alive, don’t gamble. Ask. Always ask. You’ve got nothing to lose but your life.

Joanne Beriña December 4, 2025 AT 19:26

Why are we letting foreign factories make our medicine? The FDA doesn’t even inspect half their plants. This isn’t about science - it’s about letting China and India control our healthcare. We need American-made drugs. Period.

ABHISHEK NAHARIA December 5, 2025 AT 14:14

The epistemological framework of bioequivalence is fundamentally reductionist. It quantifies pharmacokinetic parameters while neglecting the ontological uniqueness of individual metabolic phenotypes. The neoliberal imperative of cost-efficiency has colonized clinical decision-making, reducing therapeutic outcomes to actuarial metrics. One cannot reduce human physiology to a confidence interval.

Hardik Malhan December 6, 2025 AT 17:05

NTI drugs require therapeutic monitoring. If your provider isn’t checking levels after a switch, they’re not doing their job. It’s not the generic’s fault - it’s the lack of follow-up. Labs exist for a reason. Use them.

Casey Nicole December 6, 2025 AT 17:53

Ugh I just got a generic for my antidepressant and now I feel like a hollow shell. Like my soul got swapped too. And now I have to explain to my therapist why I’m suddenly not ‘optimizing’ anymore. Like I’m not even a person anymore, just a cost center. Ugh.

Kelsey Worth December 7, 2025 AT 05:30

funny how the same people who scream ‘trust science’ when it’s about vaccines go full conspiracy mode when it’s about generics. 🙄

the FDA doesn’t approve junk. if your doc says don’t switch, fine. but don’t pretend every generic is a death trap.

Richard Elias December 7, 2025 AT 13:31

Anyone who says generics are dangerous hasn’t read the studies. 90% of people don’t notice a difference. The rest are either hypochondriacs or doctors who don’t trust their own patients. You want brand-name? Pay for it. Don’t make the rest of us subsidize your fear.

Write a comment