When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy in Berlin, Paris, or Warsaw, you might assume it’s the same everywhere. But behind that simple label is a complex, fragmented system of rules that varies wildly from one EU country to another. Even though the European Union is built on harmony, when it comes to generic medicines, the system feels more like a patchwork quilt stitched together by 27 different national authorities. This isn’t just bureaucracy-it’s a major factor in whether a life-saving drug reaches patients on time, at a fair price, or at all.

The Four Paths to Market: How Generics Get Approved in the EU

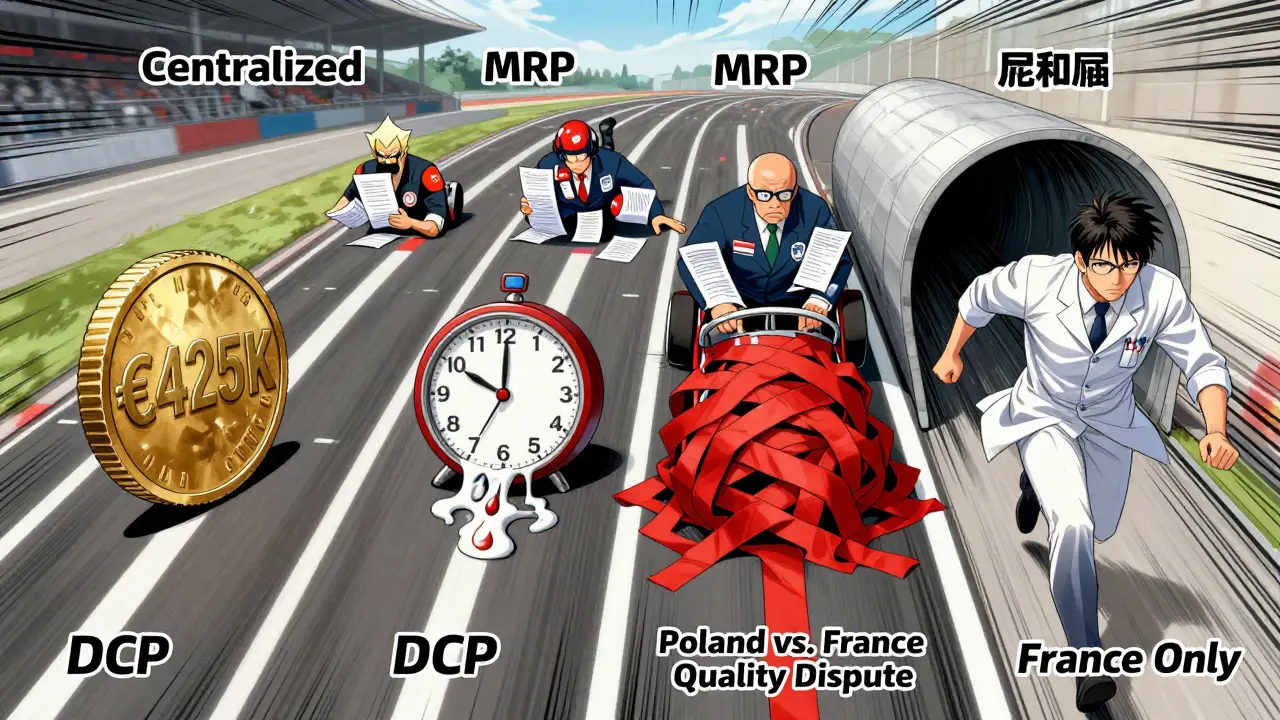

Generic drug makers in Europe don’t have one route to market-they have four. Each comes with different costs, timelines, and risks. The Centralized Procedure is the fastest way to get approval across all 27 EU countries plus Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway. It’s used for about 15% of generic applications and requires one single application to the European Medicines Agency (EMA). If approved, the medicine can launch everywhere at once. But it’s expensive: application fees alone cost around €425,000, and with consultancy and study costs, total spending often hits €1.2-1.8 million. That’s only worth it for high-volume, high-value generics-think drugs that could sell over €250 million annually across the EU.

The Mutual Recognition Procedure (MRP) is the most popular, used in 42% of cases. Here, a company gets approval first in one country (the Reference Member State), then asks others to accept it. Sounds simple, right? In practice, it’s messy. National authorities often add their own requirements-extra data, different documentation, delayed reviews. A 2024 IQVIA analysis found that while the official timeline is 90 days, the real average is 132.7 days. Teva’s experience with generic rosuvastatin in 2023 showed how one country’s pricing delays can hold up launches in others, even after the drug is technically approved.

The Decentralized Procedure (DCP) lets companies apply to multiple countries at the same time, without prior approval anywhere. It’s meant to speed things up, but it’s the most chaotic. A 2024 GMDP Academy case study found that 37% of DCP applications face delays longer than six months. Why? Eastern European regulators sometimes interpret quality standards differently than Western ones. A stability test that’s fine in France might be rejected in Poland. The result? Generic manufacturers spend months chasing inconsistent feedback.

Finally, there’s the National Procedure. Only 5% of generics use this path, and it’s usually because a company wants to target just one market-like France or Germany-with high reimbursement rates. But it’s slow: 180 to 240 days on average. And it defeats the whole point of EU-wide harmonization. Accord Healthcare found in 2024 that a national application in France took 197 days, while an MRP for the same drug across five countries took just 142.

What Makes a Generic ‘Approved’? Bioequivalence and Beyond

No matter which path a company takes, the core requirement is the same: prove the generic is identical to the original. That means matching the active ingredient exactly-same chemical structure, same dose, same form (tablet, injection, inhaler). But it’s not enough to just list ingredients. The generic must also be bioequivalent: meaning it gets absorbed into the bloodstream at the same rate and to the same extent as the brand-name drug.

The EMA requires two key metrics-Cmax (peak concentration) and AUC (total exposure)-to fall within 80.00% to 125.00% of the original drug’s values. That’s not a suggestion; it’s a hard rule. And it’s not easy to prove. For simple pills, studies take 6-8 months. For complex products like inhalers or topical creams, it can take over a year. Germany’s BfArM, for example, demands extra pharmacodynamic studies for inhalers that other countries don’t require. That’s why 68% of generic manufacturers surveyed by the ABPI in 2025 listed inconsistent national bioequivalence rules as their biggest headache.

The 2025 Pharma Package: A Game-Changer

In June 2025, the EU finalized its biggest overhaul of generic drug rules in 20 years. The so-called Pharma Package isn’t just tweaking the system-it’s rebuilding it. The biggest change? The expanded Bolar exemption. Before, generic companies could only start pricing and reimbursement talks two months before a patent expired. Now, they can start six months earlier. That might sound minor, but it’s huge. REMAP Consulting’s 2025 model shows this alone could shave 4.3 months off average market entry time. It also gives payers more leverage: hospitals and insurers can start negotiating prices before the generic even hits shelves, which could cut launch prices by 12-18%.

Another major shift: regulatory data protection is being shortened. Previously, innovators had 10 years of protection (8 years data + 2 years market exclusivity). Now, it’s 8 years data + 1 year market exclusivity-with a possible 2-year extension if the drug meets public health goals. This means generics can enter sooner. Evaluate Pharma estimates this will speed up entry for 78 high-value biologics currently in development.

But not everyone’s happy. Professor Panos Kanavos from LSE Health warns that the 1-year default market protection might discourage investment in complex generics-like biosimilars for rare diseases-because the return isn’t worth the cost. Meanwhile, the €490 million sales threshold for Transferable Exclusivity Vouchers could hurt mid-sized companies that can’t reach that level but still need time to recoup R&D.

Real-World Impact: Who Wins, Who Loses?

Indian manufacturers are winning. In 2024, they secured 38% of all EU generic approvals, up from 29% in 2020. Their low-cost production and agility let them compete where European firms struggle. Meanwhile, European giants like Sandoz and Viatris are doubling down on the Centralized Procedure. Sandoz’s launch of its generic version of Novartis’s Cosentyx in Q2 2025 was a textbook example: simultaneous EU-wide availability, 11 months faster than MRP would have allowed.

But smaller players are getting squeezed. Mylan (now Viatris) reported in its 2024 annual report that MRP coordination delays added €3.2 million in carrying costs per high-value launch. Accord Healthcare’s regulatory head Maria Papadopoulou said at the 2025 EGA conference that every national objection resets the 180-day clock. That unpredictability makes supply chain planning nearly impossible.

And then there’s the obligation to supply rule, introduced in the 2025 reforms. It requires companies to ensure “sufficient quantities” of generics are available. Sounds good-until you realize each country defines “sufficient” differently. Some demand stockpiles. Others just want regular shipments. Professor Kanavos argues this could create artificial shortages in smaller markets where manufacturers see little profit.

What’s Next? The Quiet Changes That Matter

Beyond the big headlines, smaller changes are quietly reshaping the industry. By 2026, all product information must be submitted electronically in XML format (ePI). That’s not just paperwork-it’s a €180,000-250,000 IT upgrade for most companies. The EMA’s online Q&A portal is updated quarterly, but 58% of manufacturers say national authorities still contradict EMA guidance, especially on impurity limits for older reference drugs.

The Critical Medicines Act of March 2025 adds another layer: mandatory stockpiling of 200 essential generics. This improves supply security but adds new compliance costs. Meanwhile, the US-EU Framework Agreement, effective September 2025, could affect ingredient tariffs-though no one yet knows how much it’ll impact generic manufacturing costs.

By 2028, the EU’s generic prescription share is expected to rise from 65% to 69.2%. That’s good news for patients and payers. But behind that number are thousands of hours of regulatory work, millions in compliance costs, and dozens of conflicting national rules. The system is getting smarter, faster, and more connected-but it’s still not seamless.

What This Means for Patients and Providers

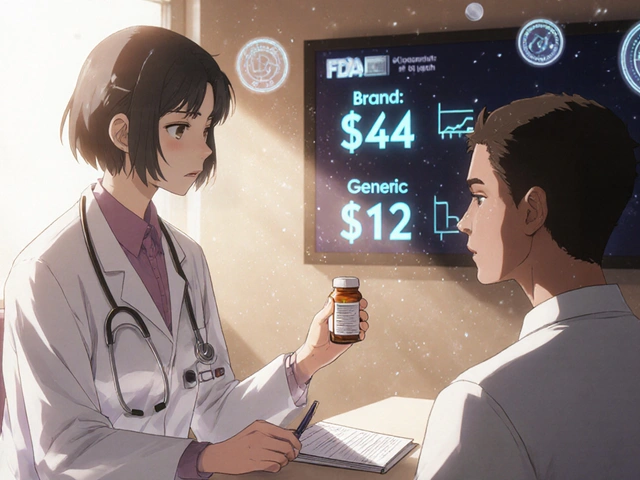

For patients, the goal is simple: affordable, reliable access to life-saving medicines. For doctors and pharmacists, it’s about knowing whether a generic will be available when needed. The current system delivers on price-generics account for 65% of prescriptions by volume-but not always on timing. Delays of over 11 months on average across member states mean patients in one country might get a drug months-or even years-before others.

That’s not just inconvenient. In chronic conditions like diabetes or hypertension, even a few weeks’ delay can mean worse outcomes. The 2025 reforms aim to fix this, but success will depend on how well national authorities actually implement the rules. Will Germany stop adding extra tests? Will Poland align its quality standards with the EMA? Until then, the EU’s promise of a unified market remains just that-a promise.

How long does it take to get a generic drug approved in the EU?

The timeline varies by approval pathway. The Centralized Procedure takes about 277 days total (210 days for EMA assessment + 67 days for European Commission approval). The Mutual Recognition Procedure averages 132.7 days, but often stretches longer due to national delays. The Decentralized Procedure takes around 247 days on average, with frequent delays from inconsistent national reviews. The National Procedure can take 180-240 days. Under the 2025 reforms, the Bolar exemption allows companies to begin pricing talks 6 months before patent expiry, which can cut overall market entry time by up to 4.3 months.

Why are generic drugs cheaper in some EU countries than others?

Price differences come from national reimbursement policies, not manufacturing costs. While the active ingredient is identical, each country sets its own price and reimbursement level. Germany may pay more for a generic than Romania, even if both have the same product. This creates parallel trade, where generics are bought in low-price countries and resold in high-price ones. The 2025 Pharma Package doesn’t change this, so price gaps will persist unless EU-wide pricing rules are introduced.

Can a generic drug be rejected after it’s approved in one country?

Yes. Under the Mutual Recognition and Decentralized Procedures, other countries can object to approval based on national concerns-even if the EMA has approved it. These objections can be about labeling, storage conditions, or even perceived quality differences. When an objection is raised, the review clock resets, and the company must respond. This is why some generics take over two years to launch across the EU, even after initial approval.

What’s the difference between bioequivalence and therapeutic equivalence?

Bioequivalence means the generic drug is absorbed into the bloodstream at the same rate and extent as the original. Therapeutic equivalence goes further-it means the generic works the same way in the body, producing the same clinical effect. In the EU, bioequivalence is the legal standard for approval. Therapeutic equivalence is assumed based on bioequivalence, but in rare cases (like complex inhalers or extended-release tablets), differences in formulation can lead to real-world variations in effectiveness.

Are Indian generic manufacturers taking over the EU market?

They’re gaining fast. In 2024, Indian companies secured 38% of all EU generic approvals, up from 29% in 2020. Their advantage lies in lower production costs, experience with complex formulations, and aggressive pricing. European firms still hold 52% of the market, but they’re shifting toward high-value generics approved via the Centralized Procedure. The trend suggests India will continue growing its share, especially as price pressure increases and regulatory barriers for low-cost producers ease.

Posts Comments

Sam Dickison February 8, 2026 AT 16:04

Let’s be real-the EU’s generic drug system is a masterpiece of bureaucratic improvisation. Centralized Procedure? Great for big pharma. MRP? A 132-day nightmare with national regulators adding their own flavor text. And don’t even get me started on DCP-three countries approve it, Poland says ‘nope, your stability data’s sus,’ and now you’re back at square one. It’s not harmonization, it’s regulatory whack-a-mole.

The 2025 Pharma Package helps, sure, but the Bolar exemption? More like ‘Bolar-lite.’ Six months early? Cool. But if France still demands extra pharmacokinetic studies for a simple tablet, you’re not saving time-you’re just paying for more consultants.

And don’t pretend Indian manufacturers are ‘taking over.’ They’re just better at playing the game. Lower labor, fewer regulatory tantrums, and zero ego about national pride. Meanwhile, Sandoz is out here spending $1.8M on a single centralized filing like it’s a luxury SUV. The system rewards scale, not efficiency. That’s not innovation. That’s survival.

Brett Pouser February 8, 2026 AT 20:07

I love how we talk about ‘harmonization’ like it’s some noble EU ideal, but the truth is, every country still treats generics like their own little sovereign kingdom. Germany’s BfArM wants extra studies? Fine. Poland rejects a stability test because it ‘doesn’t feel right’? Also fine. It’s like the EU says, ‘Go ahead, be unified,’ then hands each member state a remote and says, ‘Change the channel whenever you want.’

And honestly? Patients don’t care about bioequivalence percentages. They care if their insulin is in stock. If a guy in rural Romania waits six months longer than his neighbor in Berlin for the same pill? That’s not a policy gap. That’s a moral one.

Maybe instead of tweaking approval paths, we should just say: ‘One standard. One price. One shelf.’ No exceptions. No ‘national concerns.’ Just medicine. Simple. Human. Done.

Write a comment