When a patient switches from an originator biologic to a biosimilar, it’s not just a change in brand name-it’s a shift in how a life-changing treatment is delivered. For people managing chronic conditions like rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, or inflammatory bowel disease, this switch can mean the difference between affordable care and unaffordable bills. But what actually happens in the body? And why do some patients worry, even when doctors say it’s safe?

What Is a Biosimilar, Really?

A biosimilar isn’t a generic drug. That’s a common misunderstanding. Generics are exact chemical copies of small-molecule drugs like aspirin or metformin. Biosimilars are different. They’re complex proteins made from living cells-think of them as very close cousins, not twins, of the original biologic. The originator drug, like Humira (adalimumab) or Remicade (infliximab), is made using living cells in a lab. The biosimilar uses the same process, but no two batches of living-cell products are identical. Regulatory agencies like the FDA and EMA require biosimilars to match the original in structure, function, and clinical effect. They don’t need to be identical-they just need to show no clinically meaningful differences in safety, purity, or potency.

The first U.S. biosimilar, Zarxio (filgrastim-sndz), was approved in 2015. Since then, 37 biosimilars have been cleared by the FDA, mostly targeting tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors. These drugs treat conditions that affect millions: 1.5 million Americans have rheumatoid arthritis alone. Without biosimilars, many couldn’t afford treatment at all.

What Happens When You Switch?

Switching from an originator to a biosimilar isn’t a gamble-it’s backed by data. A major 2020 study called NOR-Switch followed 481 patients with inflammatory arthritis who switched from infliximab to its biosimilar, CT-P13. At one year, 52.6% were still on the biosimilar. The original drug had 60% retention. That difference? Not statistically significant. In other words, it wasn’t a real drop in adherence. More recent data from 2023 shows even better results: 89.2% of patients stayed on therapy after switching multiple times over two years.

Real-world evidence from the DANBIO registry in Denmark, which tracks over 10,000 patients, found that 68% reported no issues after switching from originator infliximab to CT-P13. Similar results popped up in studies of adalimumab biosimilars: retention rates were nearly identical to the original. A 2021 study in psoriasis patients showed 79% stayed on the biosimilar after a year-compared to 81.3% on the originator before the switch.

Even the science behind how the drug works stays the same. Trough levels-the amount of drug in your blood between doses-didn’t change meaningfully after switching. One study measured infliximab levels before and after switching from originator to two different biosimilars. The average level was 4.3 μg/mL before and 4.1 μg/mL after. That’s a 5% drop, not a clinical concern. Immunogenicity-the risk of your body making antibodies against the drug-also didn’t spike. One study found just 3 cases of new antibodies per 100 patient-years across multiple switches.

Why Do Some Patients Stop Taking It?

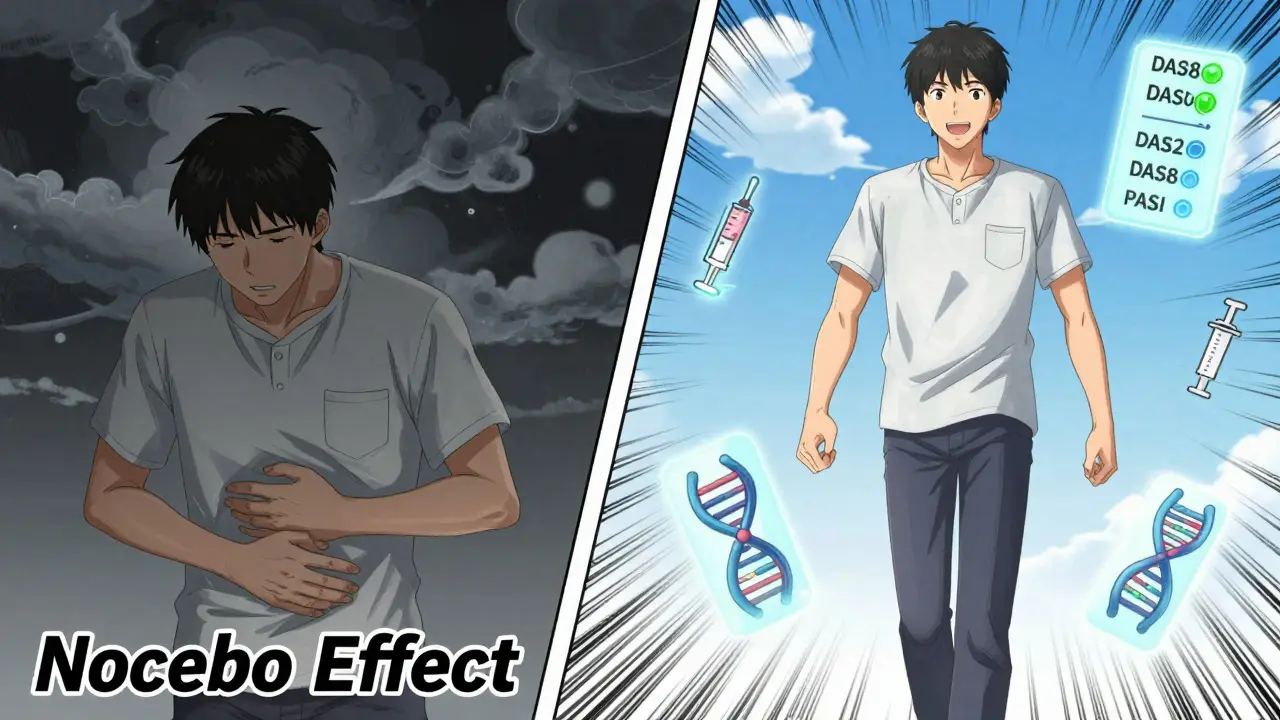

If the science says it’s safe, why do 4% to 18% of patients stop after switching? The answer isn’t always medical-it’s psychological.

A 2021 study in Frontiers in Psychology found that 32.7% of patients reported new or worsening symptoms after switching-even though lab tests showed no change in disease activity. This is called the nocebo effect: expecting harm leads to feeling harm. Patients who had been on the original drug for years often believed the biosimilar was “weaker” or “less reliable.” One Reddit thread from a patient with rheumatoid arthritis read: “I switched to the biosimilar and suddenly my knees felt heavier. I didn’t feel like myself.” Lab tests? Normal. Disease score? Stable. But the feeling? Real.

Other reasons for stopping include injection-site reactions (7.8% in adalimumab biosimilar studies) or vague complaints like fatigue or headaches. In one study, 12.6% of patients discontinued after switching from etanercept to its biosimilar-not because their arthritis got worse, but because they felt “different.”

It’s important to note: actual drug failure due to immunogenicity or loss of efficacy remains rare. Only 1.7 events per 100 patient-years were linked to true biological reasons. That’s less than 2% of all switches.

Cost and Access: The Bigger Picture

Behind every switch is a financial decision. Originator biologics cost $20,000 to $40,000 per year. Biosimilars typically launch at 15% to 35% lower prices. In 2023, Humira biosimilars entered the U.S. market at a 35% discount. That’s not just savings for insurers-it’s access for patients who were rationing doses or skipping treatments entirely.

By 2023, 85% of U.S. health plans had implemented mandatory switching policies. In Europe, biosimilar use for filgrastim reached 67% of prescriptions. These aren’t just numbers-they mean people with Crohn’s disease, psoriasis, or rheumatoid arthritis can now afford to stay on treatment long-term.

But savings aren’t automatic. In the U.S., pharmacy benefit managers and rebates often keep originator prices artificially high. That’s why adoption lags compared to Europe, where pricing is more transparent and regulated.

Switching Between Biosimilars: Is It Safe Too?

Some patients don’t just switch once-they switch again. Maybe their insurance changes. Maybe the pharmacy runs out of one biosimilar and substitutes another. Is that safe?

Yes. A 2020 study in Germany looked at 100 patients who switched from one adalimumab biosimilar (SB4) to another (GP2015). Disease activity stayed stable. No new antibodies formed. A 2022 Spanish study of IBD patients switching from CT-P13 to SB2 saw a slightly higher discontinuation rate (15.3% vs. 8.7%), but trough levels didn’t drop. That suggests the issue wasn’t the drug-it was how the switch was handled.

Here’s the key: switching between biosimilars doesn’t increase risk if the patient is stable. The EMA and FDA both agree: multiple switches don’t compromise safety. The 2023 NOR-SWITCH II extension confirmed this: patients who switched three times over 24 months still had 89% retention.

What Makes a Successful Switch?

Not every switch works well. The difference between success and failure often comes down to communication.

A 2023 study called PERFUSE showed that with proper education, discontinuation rates dropped from 18% to just 6.4%. How? Three things:

- Pre-switch counseling: At least 20 minutes with a specialist who explains what biosimilars are, how they’re made, and why the switch is safe.

- Shared decision-making: Patients aren’t told-they’re asked. “What concerns do you have?” “Would you like to meet with a pharmacist?”

- Post-switch monitoring: Checking disease activity at 3 months using tools like DAS28 for arthritis or PASI for psoriasis. Blood tests for drug levels and antibodies if needed.

Patients who felt heard were far more likely to stay on therapy. Those who felt like a “cost-cutting experiment” were more likely to quit.

Regulatory Differences Matter

The U.S. and Europe handle biosimilars differently. The FDA requires separate studies to approve a drug as “interchangeable”-meaning a pharmacist can swap it for the originator without asking the doctor. Cyltezo became the first interchangeable adalimumab biosimilar in 2024. The EMA doesn’t require this. To them, all biosimilars are switchable by default.

This creates confusion. A patient in the U.S. might get switched at the pharmacy without their doctor’s input. In the UK or Germany, the prescriber usually decides. Both approaches have pros and cons. The U.S. model increases access but risks undermining trust. The European model is more cautious but slower to scale.

What’s Next?

More than $178 billion in biologic patents are expiring by 2025. That means dozens more biosimilars are coming-for drugs used in cancer, diabetes, and autoimmune diseases. By 2030, the global biosimilar market is expected to hit $100 billion.

But the biggest challenge isn’t science. It’s perception. Patients need to know: switching isn’t a downgrade. It’s a smart, safe, and often necessary step to keep treatment affordable. The data is clear. The real question is whether our healthcare systems will prioritize patient trust as much as they do cost savings.

Final Thoughts

If you’re considering or have been asked to switch from an originator biologic to a biosimilar, here’s what you need to know:

- The science says it’s safe-multiple studies confirm no loss of effectiveness or increase in serious side effects.

- Most people feel no difference. Some do, and that’s often because of fear, not the drug.

- Cost savings are real and help more people get the treatment they need.

- Communication matters. Ask your doctor to explain why the switch is happening. Ask for a follow-up check-in.

- Switching between biosimilars is also safe if you’re stable.

There’s no perfect drug. But there is a better way to make life-changing treatments accessible. That’s what biosimilar switching is really about.

Are biosimilars the same as generics?

No. Generics are exact chemical copies of small-molecule drugs, like ibuprofen or metformin. Biosimilars are complex proteins made from living cells, so they can’t be identical to the original. But they must show no clinically meaningful differences in safety, effectiveness, or how they work in the body. Regulatory agencies require extensive testing to prove this.

Can switching cause my condition to get worse?

In clinical studies, switching from an originator biologic to a biosimilar does not increase the risk of disease flare. Large studies involving thousands of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and inflammatory bowel disease show similar disease control before and after the switch. However, some patients report feeling worse due to psychological factors-known as the nocebo effect-not because the drug stopped working.

Why do some patients stop taking biosimilars?

The most common reason isn’t medical-it’s perception. Patients may believe the biosimilar is inferior, or they experience mild side effects like injection-site reactions or fatigue. In some cases, these symptoms are linked to anxiety about the switch, not the drug itself. Studies show that with proper education and counseling, discontinuation rates drop by more than half.

Is it safe to switch from one biosimilar to another?

Yes. Multiple studies, including the NOR-SWITCH II trial, show that patients who switch between different biosimilars of the same reference drug maintain stable disease control. Drug levels in the blood and antibody formation remain consistent. The main risk comes not from the drugs themselves, but from poor communication-if patients aren’t informed or involved in the decision, they’re more likely to stop treatment.

Do biosimilars save money?

Yes. Biosimilars typically cost 15% to 35% less than the original biologic. In 2023, Humira biosimilars launched at a 35% discount in the U.S. This allows health systems to treat more patients and reduces out-of-pocket costs. In Europe, where biosimilar use is widespread, access to biologic treatments has increased dramatically.

Will my doctor need to approve every switch?

In the U.S., if a biosimilar is designated as “interchangeable,” a pharmacist can substitute it without contacting your doctor. But most switches still require a prescription change. In Europe and the UK, switches are usually decided by the prescriber. Always ask whether a switch is planned and whether you have a say in the decision.