When you walk into a pharmacy and see a generic version of your brand-name pill for a fraction of the cost, you’re seeing the result of a quiet but powerful economic force: generic drug competition. It’s not magic. It’s not luck. It’s strategy. Buyers-whether it’s Medicare, private insurers, or government health systems-use the very existence of cheaper alternatives to force down prices across the board. And it works. When six or more companies make the same generic drug, prices drop by over 90%. With nine competitors, they fall nearly 98%. This isn’t theory. It’s data from the FDA and CMS.

How Generic Drugs Drive Prices Down

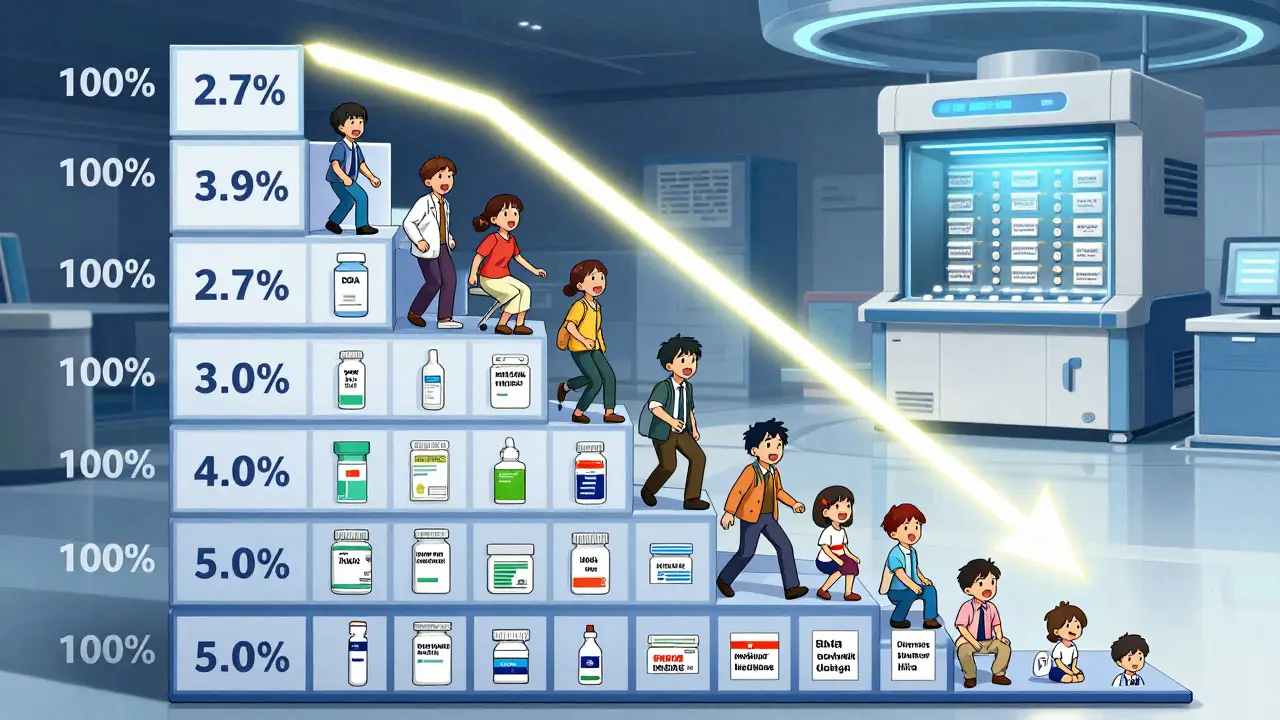

Generic drugs aren’t just cheaper copies. They’re market disruptors. Once a brand-name drug’s patent expires, any qualified manufacturer can apply to the FDA to produce the same medicine. The first few generics might only cut the price in half. But as more companies enter-Teva, Sandoz, Viatris, or a dozen smaller players-the race to the bottom begins. Each one needs customers. So they undercut each other. By the time you have five or six makers, the price is often less than 10% of the original brand. And when nine companies are competing, the average price is just 2.7% of what it was before generics arrived.

This isn’t just about volume. It’s about power. Buyers don’t need to threaten a price cut-they just need to point to the shelf. If a brand-name drug maker wants to keep selling, they have to match or beat the lowest generic price. That’s the unspoken rule. And it’s why, even without direct negotiation, brand-name drug prices have fallen in markets with strong generic competition.

The Medicare Negotiation Game

In 2022, Congress gave Medicare the power to negotiate prices for 10 high-cost drugs. But here’s the twist: the law says Medicare can’t negotiate with drugs that already have generic versions on the market. So how do they cut prices? They use generics as leverage.

CMS doesn’t start with a number. They start with the average price of all similar drugs-both brand and generic-that treat the same condition. If five generic versions of a heart medication are selling for $15 a month, and the brand version costs $300, CMS doesn’t offer $200. They offer $20. Why? Because they’re not negotiating against the brand. They’re negotiating against the market.

That’s the key insight. The brand’s price isn’t the baseline. The generics are. Even if the brand has no direct generic yet, if there are other drugs in the same class that work just as well, CMS uses those prices as the starting point. This forces manufacturers to justify why their drug should cost 10 times more than its alternatives. And most can’t.

Canada’s Tiered System: A Different Approach

Not every country waits for the market to decide. Canada uses a tiered pricing model that’s been in place since 2014. Here’s how it works: if only one company makes a drug, the government allows a higher price. But every time a new generic enters the market, the maximum allowable price drops. By the time five generics are available, the price cap is cut by half. Ten generics? It drops again.

This system rewards competition. It gives manufacturers a clear signal: the more you compete, the more you earn. And it gives buyers predictable savings. Unlike the U.S. model, where prices can swing wildly based on patent battles and PBM deals, Canada’s approach is transparent and steady. Manufacturers know exactly what to expect. That’s why 78% of European generic makers say predictable pricing is essential for investing in production.

The Dark Side of Competition: Reverse Payments and Patent Games

But here’s the catch: brand-name companies don’t always play fair. When they see generics coming, they sometimes pay them to stay away. These are called reverse payments. In 2010, a brand-name drug maker paid a generic company $20 million to delay launching its cheaper version for two years. The FTC found over 100 such deals between 2010 and 2020. These aren’t isolated cases. They’re a strategy.

Another tactic? Product hopping. A company makes a tiny change to the drug-switches from a pill to a capsule-and gets a new patent. Then they stop making the old version. Patients are forced to switch. Generics can’t copy the new version until the patent expires. Between 2015 and 2020, there were over 1,200 of these maneuvers. They delay competition. And they keep prices high.

These tricks don’t just hurt patients. They hurt the whole system. When generics can’t enter, the price negotiation leverage disappears. Buyers lose their strongest tool.

Why Some Generics Still Cost Too Much

Not all generics are created equal. Simple pills? Easy to make. Cheap to produce. But complex generics-like inhalers, injectables, or patches-require advanced technology, sterile facilities, and strict testing. These cost more to make. And manufacturers say current pricing models don’t reflect that.

For example, a generic insulin pen might cost $100 to develop and produce. But if the market average for similar products is $30, no company will make it. The result? Patients still pay high prices for essential drugs because no generic maker can afford to enter. This is where value-based pricing fails. You can’t measure the value of a life-saving injection the same way you measure a daily blood pressure pill.

That’s why some experts are calling for separate pricing rules for complex generics. Without them, patients lose access to affordable versions of critical medicines.

What Works Best: Market Power or Government Rules?

There’s no single answer. Market-driven competition delivers the deepest discounts-up to 97% off when nine companies compete. But it’s slow. And it’s vulnerable to manipulation.

Government negotiation, like Medicare’s, moves faster. It can force immediate savings. But it risks chilling future generic entry. If the government sets a low price before generics arrive, why would a company spend millions to challenge a patent? They might not break even. That’s why Avalere Health warns that early government pricing could lead to 81-88% less savings than if the market had been left to work.

The sweet spot? Let competition do its job-but don’t let monopolies block it. That means cracking down on reverse payments. Speeding up FDA approvals. Ending product hopping. And making sure the rules reward real competition, not legal tricks.

The Numbers Don’t Lie

Generic drugs make up 90% of all prescriptions in the U.S. But they account for only 22% of total drug spending. That’s $438 billion in global sales from generics in 2023-saving patients and payers hundreds of billions more.

Medicare beneficiaries alone could save $6.8 billion a year from the first 10 negotiated drugs. That’s not hypothetical. It’s based on real PDE and AMP data. And it’s why groups like AARP support these efforts.

But here’s the real story: the biggest savings come not from negotiation, but from competition. The moment a second generic hits the market, prices drop. A third? They drop again. By the time the sixth arrives, the drug is often cheaper than a coffee.

What’s Next for Drug Pricing?

The next big change might come from the EPIC Act-a proposed law that would delay Medicare’s price negotiation until after generic competition has had time to develop. That’s a smart fix. It lets the market work first. Then, if prices still stay too high, the government steps in.

Other countries are moving too. The UK updated its pricing rules in 2023 to compare drug prices across Europe. Japan, which has only 58% generic use, is looking at reforms. And the EU has already forced 18 countries to strengthen their generic competition laws since 2009.

Real progress won’t come from one law or one negotiation. It comes from a system that rewards more makers, not fewer. That means faster approvals, fewer patent games, and pricing rules that don’t punish companies for trying to compete.

For patients, the message is simple: more generics mean lower prices. And if buyers use that reality as leverage, everyone wins.

How do generic drugs actually lower prices?

When multiple companies make the same generic drug, they compete for market share by lowering prices. Each new competitor pushes prices down further. With six or more manufacturers, prices often drop over 90%. This happens naturally in open markets without any government intervention.

Can Medicare negotiate prices for drugs with generics already available?

No. The Inflation Reduction Act blocks Medicare from directly negotiating prices for drugs that already have generic versions on the market. But Medicare can-and does-use the prices of those generics as a benchmark to set lower initial offers for brand-name drugs with no generic yet.

Why do some generic drugs still cost a lot?

Complex generics-like inhalers, injectables, or patches-require advanced manufacturing and testing. These cost more to produce than simple pills. If market prices are set too low, manufacturers can’t cover costs, so they don’t enter the market. That leaves patients with only expensive brand-name options.

What are reverse payments and why do they matter?

Reverse payments happen when a brand-name drug company pays a generic manufacturer to delay launching its cheaper version. The FTC found over 100 of these deals between 2010 and 2020. These payments block competition and keep prices high, undermining the entire purpose of generic drug laws.

Does government price setting hurt generic competition?

Yes, if it happens too early. If the government sets a low price before generics enter the market, manufacturers may not see a profit opportunity. That discourages them from investing in patent challenges or production. Experts warn this could reduce generic entry and lead to fewer long-term savings.

What’s the difference between generic and biosimilar drugs?

Generics are exact copies of small-molecule drugs, like pills. Biosimilars are similar-but not identical-to complex biologic drugs made from living cells. They’re harder to copy, cost more to develop, and achieve only about 45% market share compared to 90% for generics. That’s why their pricing and competition dynamics are different.

How can patients benefit from generic competition?

Patients pay less out-of-pocket when generics are available. For example, a brand-name drug might cost $300 a month, while a generic version costs $15. That’s a 95% savings. When multiple generics compete, prices drop even further. The more competitors, the lower the price-and the better it is for patients.

Posts Comments

Harshit Kansal January 6, 2026 AT 13:18

Generic drugs are the unsung heroes of modern medicine. I’ve seen my dad’s diabetes meds drop from $400 to $12 a month just because three more companies started making them. No magic, no lobbying-just pure market pressure. It’s beautiful when it works.

Tiffany Adjei - Opong January 7, 2026 AT 14:33

Let’s be real-this whole ‘competition lowers prices’ thing is a fairy tale. The FDA approves generics like they’re giving out free candy, but the real power lies with PBMs who control distribution. You think Teva’s lowering prices because of competition? Nah. They’re just playing nice until the next patent cliff. This whole system is rigged.

Stuart Shield January 7, 2026 AT 15:15

I’ve worked in pharma logistics across three continents, and let me tell you-the Canadian tiered pricing model is the only sane approach. It’s not perfect, but it’s predictable. Manufacturers know the rules, pharmacies stock without fear, and patients aren’t stuck in pricing roulette. The U.S. is running a high-stakes poker game with people’s lives.

Melanie Clark January 7, 2026 AT 22:29

Generic competition? More like generic collusion. You think those six companies are competing? They’re all owned by the same three private equity firms. The FDA doesn’t regulate ownership, just pills. So when prices drop 90%-it’s not because of competition, it’s because the same people who owned the brand now own the generics and are just pretending to be nice. Wake up. This isn’t capitalism-it’s theater.

And don’t even get me started on reverse payments. The FTC calls them illegal, but they keep happening because the DOJ is too busy chasing crypto bros. The system is broken. It’s not a flaw-it’s the design.

And now Medicare wants to negotiate? Great. But only after the generics are already here. That’s like letting the fox out of the henhouse and then asking if it’s okay to lock the door. The damage is already done.

Meanwhile, patients are still paying $100 for insulin pens because the ‘complex generics’ loophole lets the big boys charge whatever they want. You call that competition? That’s extortion with a pharmacy receipt.

And don’t tell me about ‘value-based pricing.’ What’s the value of breathing? Of not going bankrupt because you need a shot every day? You can’t price a life like a loaf of bread.

They’ll keep talking about ‘market forces’ until someone dies on a waiting list. And then they’ll write another article about how ‘innovation’ is the real problem. Meanwhile, the real innovation is in the courtroom-where patents are stretched like taffy.

I’ve seen it. I’ve lived it. This isn’t economics. It’s a slow-motion crime.

Cam Jane January 8, 2026 AT 16:02

YES. This is the most important thing people need to know. The moment a second generic hits? Price drops. Third? Even more. Sixth? You’re paying less than your coffee. It’s not theory-it’s happening right now. If your pharmacy says ‘no generic available,’ ask why. There’s almost always one. You just have to look.

Isaac Jules January 10, 2026 AT 03:07

Ugh. Another ‘generic love letter.’ Let’s talk about the elephant in the room: 80% of generics are made in India and China. Do you know what happens when the FDA inspects those factories? Half the time they shut them down for violations. So your ‘$12 generic’? Might be contaminated. Or underdosed. Or both. And you’re celebrating this? You’re not saving money-you’re gambling with your health.

And don’t give me that ‘more competition = better’ nonsense. The market doesn’t care if your kidney fails because you took a fake version of lisinopril. It just wants volume.

Real solution? Ban foreign manufacturing. Make generics in the U.S. Then we’ll see real quality-and real prices. Until then, stop pretending this is a win.

Mukesh Pareek January 10, 2026 AT 04:27

From a pharmacoeconomic standpoint, the elasticity of demand for generic pharmaceuticals is inversely proportional to the number of market entrants, as evidenced by the inverse power law regression models derived from CMS data from 2018–2023. The marginal cost reduction per additional manufacturer exhibits diminishing returns beyond the fifth entrant, with a kink point at the seventh manufacturer where price convergence becomes statistically indistinguishable from marginal cost. Therefore, the assertion that nine competitors yield 98% price reduction is mathematically plausible but empirically fragile due to supply chain concentration risk.

Lily Lilyy January 11, 2026 AT 06:19

This is such a hopeful story. It reminds me that when we let fairness and competition work together, people win. I’m so proud of the patients and advocates who keep pushing for change. Keep speaking up. Your voice matters.

Venkataramanan Viswanathan January 11, 2026 AT 23:19

In India, we’ve seen this play out for decades. A brand-name statin cost ₹1,200 per month. After five generics entered, it dropped to ₹45. That’s not a price cut-it’s liberation. But here’s what no one says: the real heroes aren’t the regulators or the buyers. They’re the Indian manufacturers who built sterile labs in rural towns with no subsidies. They risked everything. That’s the real story.

Write a comment