Drug shortages are hitting hospitals harder than ever

In 2025, over 277 drugs remained in short supply across the U.S., according to Global Biodefense. These aren’t rare specialty meds - they’re the basics: antibiotics, chemotherapy drugs, anesthetics, and saline solutions. Hospitals are forced to scramble. Pharmacists spend hours tracking down alternatives. Nurses administer unfamiliar doses. Patients delay cancer treatments or switch to less effective pills. And behind it all is a federal system that’s trying to react - but still missing the root causes.

The Strategic Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients Reserve (SAPIR)

The biggest federal move in recent years is the Strategic Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients Reserve, or SAPIR. Signed into action in August 2025, this program stocks up on the raw chemical building blocks - APIs - needed to make 26 critical drugs. Why APIs? Because they’re cheaper to store, last 3-5 years longer than finished pills or injections, and are easier to transport than bulky final products. The goal: if a factory in India shuts down or a hurricane hits a plant in New Jersey, the U.S. can quickly turn these stored chemicals into life-saving medicine.

But here’s the catch: the 26 drugs on the list cover only a fraction of what’s actually in short supply. Oncology drugs alone make up 31% of all shortages, yet only 4% of SAPIR’s targets are cancer meds. Experts like Dr. Luciana Borio call this approach "reactive," not preventative. Stockpiling helps in a crisis, but it doesn’t fix why the shortages happen in the first place.

Why are drug shortages so common?

The problem isn’t just one bad supplier. It’s a broken system. About 80% of the active ingredients in U.S. drugs come from China and India. Manufacturing is concentrated: just five facilities produce 78% of all sterile injectables. If one of them has a quality control issue - like contaminated water or a faulty filter - dozens of drugs vanish overnight.

And there’s no profit incentive to fix it. Many of these drugs - like penicillin or heparin - cost pennies to make. Companies won’t spend millions building backup factories for medicines that barely earn a few cents per dose. The FDA approved 56 new manufacturing sites in 2024, but 42% of them were overseas. Even with federal grants, reshoring production is slow. It takes 28-36 months to get FDA approval for a new U.S.-based API plant. In the EU, it’s 18-24 months.

What the FDA actually does during a shortage

The FDA doesn’t just sit back. When a shortage hits, they work directly with manufacturers. In 2018-2020, they helped resolve the massive saline shortage affecting 90% of U.S. hospitals by fast-tracking inspections and allowing temporary imports. Today, they resolve about 85% of shortages this way.

They also run the Drug Shortage Database - a public tool tracking over 1,200 past and current shortages. But compliance is weak. Manufacturers are legally required to report potential shortages six months in advance. Yet only 58% do. Small companies - under 50 employees - are even worse, with 82% failing to report. That means hospitals often find out about a shortage the same day it hits shelves.

In November 2025, the FDA launched an AI-powered monitoring system that analyzes 17 data streams - from shipping logs to hospital purchase patterns - to predict shortages 90 days ahead with 82% accuracy. It’s promising. But it’s still new, and hospitals need better tools to use the data.

Legislation on the table: H.R.5316 and the Drug Shortage Prevention Act

Congress is debating two major bills. H.R.5316, the Drug Shortage Act, would let pharmacists more easily use compounded versions of shortage drugs - a lifeline for cancer patients when the branded version disappears. It also gives the FDA more power to require manufacturers to report supply risks.

The bipartisan Drug Shortage Prevention and Mitigation Act proposes a different fix: Medicare payments to hospitals that keep backup suppliers on standby. Right now, hospitals lose money if they stockpile extra drugs. This bill would reward them for being prepared. The American Hospital Association supports it, saying hospitals spend an average of $1.2 million a year just managing shortages.

But the Congressional Budget Office estimates H.R.5316 will reduce shortages by only 15-20% at a cost of $740 million over five years. That’s less than 0.1% of total U.S. drug spending. Critics argue it’s not enough.

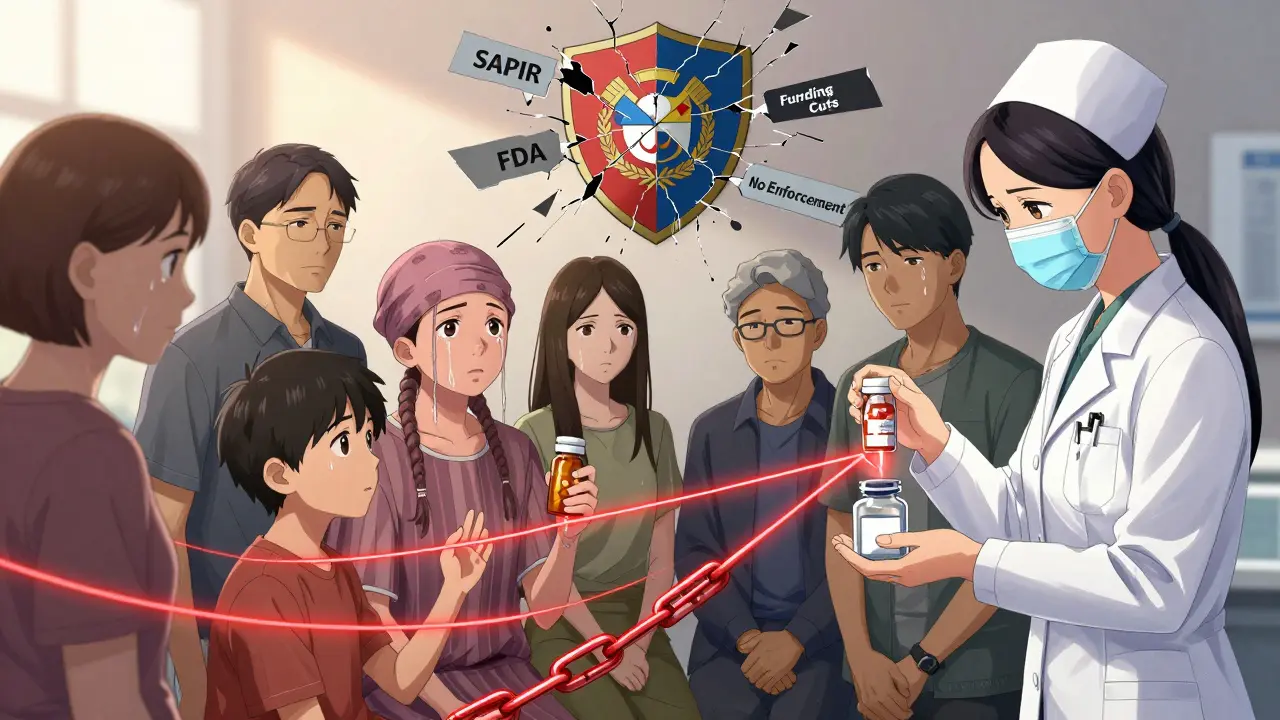

The funding gap: cuts to preparedness programs

Here’s the contradiction: while the government is spending billions on the SAPIR reserve, it’s slashing other critical programs. The 2026 HHS budget cuts $1.2 billion from FEMA’s emergency response and $850 million from state public health grants. Funding for BARDA - the agency that helped develop new manufacturing tech - dropped 22% from 2024 to 2025.

Meanwhile, the FDA issued only 17 warning letters for failure to report shortages between 2020 and 2024. The EU issued 142 under similar rules. Without enforcement, rules mean little.

The Government Accountability Office found that only 35% of ASPR’s recommended shortage-prevention actions have been adopted across federal agencies. States aren’t doing much better: only 28 out of 50 have set up the supply chain mapping tools required by the 2025 HHS Action Plan. Rural hospitals, already short on staff and tech, are falling further behind.

What’s really working - and what’s not

One bright spot: the FDA’s Early Notification Pilot Program. Hospitals that report early warning signs of shortages see their duration drop by 28%. That’s huge. But the current administration has weakened mandatory reporting rules, making this program less effective.

Second-source manufacturing is another key solution. If two companies make the same drug, one can pick up the slack if the other fails. The FDA just opened expedited review paths for second-source applicants. Fourteen companies are already in line to make backup versions of eight critical drugs by mid-2026. That’s progress.

But the market is still dominated by three companies that control 68% of sterile injectables. That’s a single point of failure waiting to happen.

The human cost: patients, pharmacists, and nurses on the front lines

Behind every shortage statistic is a person. A cancer patient skipping doses because their chemo drug is unavailable. A nurse giving a child an unfamiliar antibiotic because the standard one ran out. A pharmacist spending 10+ hours a week tracking down vials from five different suppliers.

According to the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, 41% of pharmacists have experienced a near-miss medication error because of a shortage substitution. Patients for Affordable Drugs found that 29% of Americans skipped doses due to unavailability - not cost, just lack of supply. In one Reddit thread, a pharmacist wrote: "We compounded cisplatin from raw powder last week. No one should have to do that."

What’s next? The path forward

Stockpiling APIs helps in emergencies. But long-term, the U.S. needs to fix the economics of drug production. The government must pay manufacturers more for low-margin essential drugs - or subsidize their backup capacity. It needs to shorten approval timelines for domestic plants. It needs to enforce reporting rules. And it needs to stop cutting preparedness budgets while claiming to solve the crisis.

The EU reduced shortages by 37% between 2022 and 2024 by mandating national stockpiles and creating a centralized monitoring system. The U.S. could do the same. But right now, the pieces are scattered. The tools exist. The data is there. What’s missing is the coordinated will to use them.

What drugs are most commonly in short supply?

Sterile injectables make up 73% of all drug shortages. These include antibiotics like vancomycin, chemotherapy drugs like cisplatin, anesthetics like propofol, and IV fluids like saline. Oncology drugs account for 31% of shortages, even though they’re only 4% of the government’s SAPIR priority list. Many of these are low-cost, high-volume medications that manufacturers avoid making because profits are slim.

How does the FDA know when a drug is running low?

Manufacturers are legally required to notify the FDA six months before a potential shortage. But only 58% comply - and small companies are far worse, with 82% failing to report. The FDA now uses AI to predict shortages by analyzing shipping data, hospital orders, and manufacturing records. This system, launched in November 2025, forecasts shortages 90 days in advance with 82% accuracy, but hospitals still rely heavily on manufacturer reports.

Why can’t the U.S. just make more drugs domestically?

It’s expensive and slow. Building a new API plant in the U.S. takes 28-36 months for FDA approval. In the EU, it’s 18-24 months. Plus, many essential drugs have tiny profit margins - sometimes just a few cents per dose. Companies won’t invest millions to build backup factories for products that barely earn a profit. The government has offered grants, but they cover less than 5% of the $6 billion needed to fully diversify production.

Is the SAPIR program working?

It’s too early to say definitively. HHS claims SAPIR has prevented 12 potential antibiotic shortages since August 2025, but there’s no public verification. The program targets only 26 drugs, while over 277 drugs remain in shortage. Experts argue it’s a stopgap, not a solution. It helps in emergencies but doesn’t fix why shortages happen - like manufacturing concentration, weak reporting, and lack of profit incentives.

What can hospitals do right now to manage shortages?

Hospitals are using backup suppliers, switching to alternative drugs, and using compounded versions when allowed. The FDA’s Early Notification Pilot helps reduce shortage duration by 28% if hospitals report early. But many lack the staff or tech to manage this. Training pharmacists takes 40+ hours per person. Community hospitals, especially in rural areas, are struggling the most due to limited resources and outdated IT systems.