When a generic drug hits the market, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. But how do regulators make sure it actually does? For simple pills, checking the peak concentration (Cmax) and total drug exposure (AUC) was enough. But for modern formulations-slow-release painkillers, abuse-deterrent opioids, or combo drugs that release in stages-those old metrics started to miss the real story. That’s where partial AUC comes in.

Why Traditional Bioequivalence Metrics Fall Short

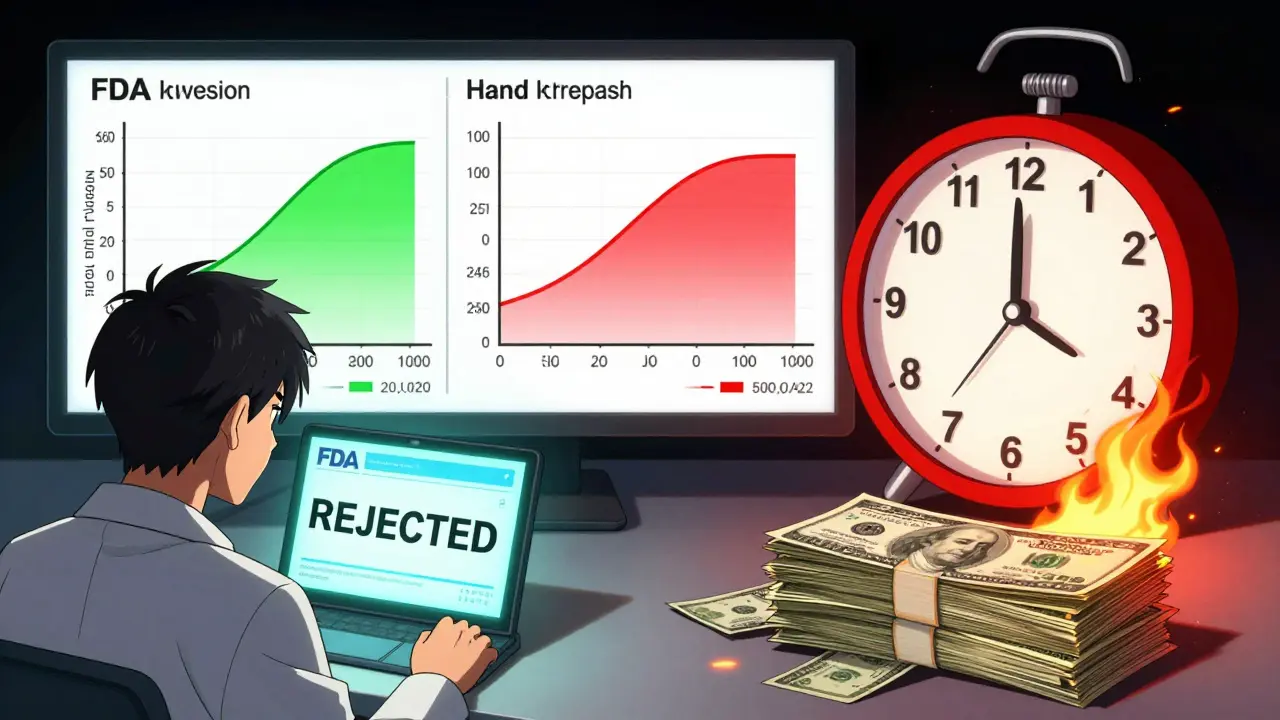

Traditionally, bioequivalence was judged using two numbers: Cmax (the highest concentration in the blood) and AUC (the total area under the concentration-time curve). These told you how much drug got into the system and how fast it peaked. But they didn’t tell you when it got there, or if the absorption pattern matched. Think of it like two cars racing. One accelerates fast and hits top speed quickly. The other creeps up slowly but ends up at the same total distance. Traditional metrics say they’re equal. But if you’re waiting for pain relief, that first car matters. The second? You’re still hurting. This gap became obvious with extended-release (ER) and modified-release drugs. In 2013, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) noticed that 20% of generic candidates that passed traditional bioequivalence tests failed when they looked at early exposure. When they added fed and fasting studies together, failure rates jumped to 40%. The same thing happened in the U.S. The FDA realized: if two drugs have the same total exposure but different absorption rates, patients could have different outcomes-too little early drug, or too much too fast.What Is Partial AUC (pAUC)?

Partial AUC, or pAUC, is not a new drug. It’s a new way of measuring. Instead of looking at the entire curve from time zero to infinity, pAUC zooms in on a specific window-usually the early phase where absorption happens. The FDA defines pAUC as the area under the concentration-time curve between two time points that are clinically meaningful. For example:- From time zero to the time when the reference product peaks (Tmax)

- From time zero to when drug concentration hits 50% of Cmax

- From time zero to a fixed time like 2 hours, if that’s when the drug needs to start working

How pAUC Works: The Science Behind the Numbers

pAUC isn’t calculated like a regular AUC. There are rules. The FDA’s 2017 Quantitative Modeling Workshop laid out three main ways to define the time window:- Based on concentration thresholds-e.g., the time when drug levels exceed 10% of Cmax

- Based on Tmax-the time to peak concentration of the reference product

- Based on a fraction of Cmax-like the time until concentration reaches 50% of the maximum

When Is pAUC Required?

pAUC isn’t used for every generic drug. It’s reserved for cases where traditional metrics aren’t enough. The FDA has been clear: if a drug has a complex release profile, pAUC becomes mandatory. Here are the main types of products where pAUC is now standard:- Extended-release opioids-to ensure the early release profile matches and doesn’t allow for abuse

- Combination products-like a pill with both immediate-release and extended-release layers

- Modified-release CNS drugs-for conditions like epilepsy or Parkinson’s, where timing affects seizure control or tremor reduction

- Cardiovascular drugs-where early exposure affects heart rate or blood pressure response

Real-World Impact: Successes and Failures

The value of pAUC isn’t theoretical. There are documented cases where it saved lives. In 2021, a generic version of an extended-release oxycodone product passed standard bioequivalence tests. But when pAUC was applied, researchers found a 22% difference in early exposure. The test product released too slowly at first. Patients wouldn’t get pain relief for hours. That product was never approved. On the flip side, companies have paid the price for ignoring pAUC. FDA inspection reports from 2022 showed 17 ANDA submissions rejected because the time window for pAUC was chosen incorrectly. One company used a fixed 2-hour window, but their drug’s Tmax was 3.5 hours. The analysis was invalid. The submission was denied. Industry surveys show 63% of generic drug developers now need extra statistical help to run pAUC analyses. That’s three times more than what’s needed for standard AUC. Biostatisticians report spending 3-6 months training before they’re confident using pAUC correctly.

Implementation Challenges

The science is solid. The execution? Not so much. The biggest problem? Inconsistency. Each product-specific guidance gives slightly different instructions. Some say use Tmax. Others say use 50% Cmax. A 2022 survey found only 42% of FDA guidances clearly defined how to pick the time window. That leaves developers guessing. There’s also the cost. Increasing sample sizes from 36 to 50 subjects isn’t just a number-it’s money. One biostatistician at Teva reported adding $350,000 to a single study just to meet pAUC requirements. For small companies, that’s a dealbreaker. And global alignment? Still broken. The EMA and FDA don’t always agree on the time window. A product approved in Europe might fail in the U.S. because the pAUC cutoff was defined differently. The IQ Consortium estimates this misalignment adds 12-18 months to global drug development timelines.The Future of pAUC

The trend is clear: pAUC is here to stay. Evaluate Pharma predicts that by 2027, 55% of all new generic approvals will require pAUC analysis-up from 35% in 2022. The FDA is working on solutions. A pilot program launched in January 2023 uses machine learning to predict the best time window based on historical reference product data. The goal? Standardize the process so every developer uses the same logic. Meanwhile, specialized contract research organizations (CROs) like Algorithme Pharma are gaining ground by building proprietary pAUC tools. They now handle 18% of the complex generic study market. The bottom line? pAUC isn’t a fancy statistical trick. It’s a necessary upgrade. For drugs where timing matters, it’s the only way to make sure patients get the right dose at the right time.What is the difference between AUC and partial AUC?

Total AUC measures the entire drug exposure from the moment the drug is taken until it’s completely cleared from the body. Partial AUC (pAUC) only looks at a specific time window-usually the early phase-where absorption and initial drug levels matter most. For example, if a painkiller needs to work within an hour, pAUC focuses on the first 60 minutes, ignoring later data that doesn’t affect the patient’s experience.

Why do some generic drugs need pAUC but others don’t?

Traditional drugs-like a simple aspirin tablet-have straightforward absorption. AUC and Cmax are enough. But for complex formulations-like extended-release opioids, abuse-deterrent pills, or combo-release tablets-the timing of drug release is critical. If the early exposure doesn’t match the brand, patients might not get relief or could overdose. That’s why pAUC is required only for products where absorption rate affects safety or effectiveness.

How is the time window for pAUC determined?

The time window is based on clinical relevance. The FDA recommends linking it to a pharmacodynamic (PD) effect-like when pain relief starts or when blood pressure drops. Common methods include using the reference product’s Tmax, the time when concentration hits 50% of Cmax, or a fixed time (e.g., 2 hours). Product-specific guidances give the exact window, but only 42% of them clearly define how to pick it, leading to confusion.

Does pAUC increase the cost of generic drug development?

Yes. Because pAUC focuses on a smaller, more variable part of the concentration curve, it requires larger sample sizes-often 25-40% more subjects than traditional bioequivalence studies. For a typical study, this can add $300,000 to $500,000 in costs. It also demands specialized statistical expertise, which many companies outsource.

Is pAUC used outside the U.S. and Europe?

Currently, pAUC is primarily used by the FDA and EMA. Other regulatory agencies, like Health Canada or the PMDA in Japan, are watching closely but have not yet mandated it widely. However, as global drug development becomes more aligned, and with the FDA expanding pAUC requirements, other regions are likely to adopt it within the next 5 years.