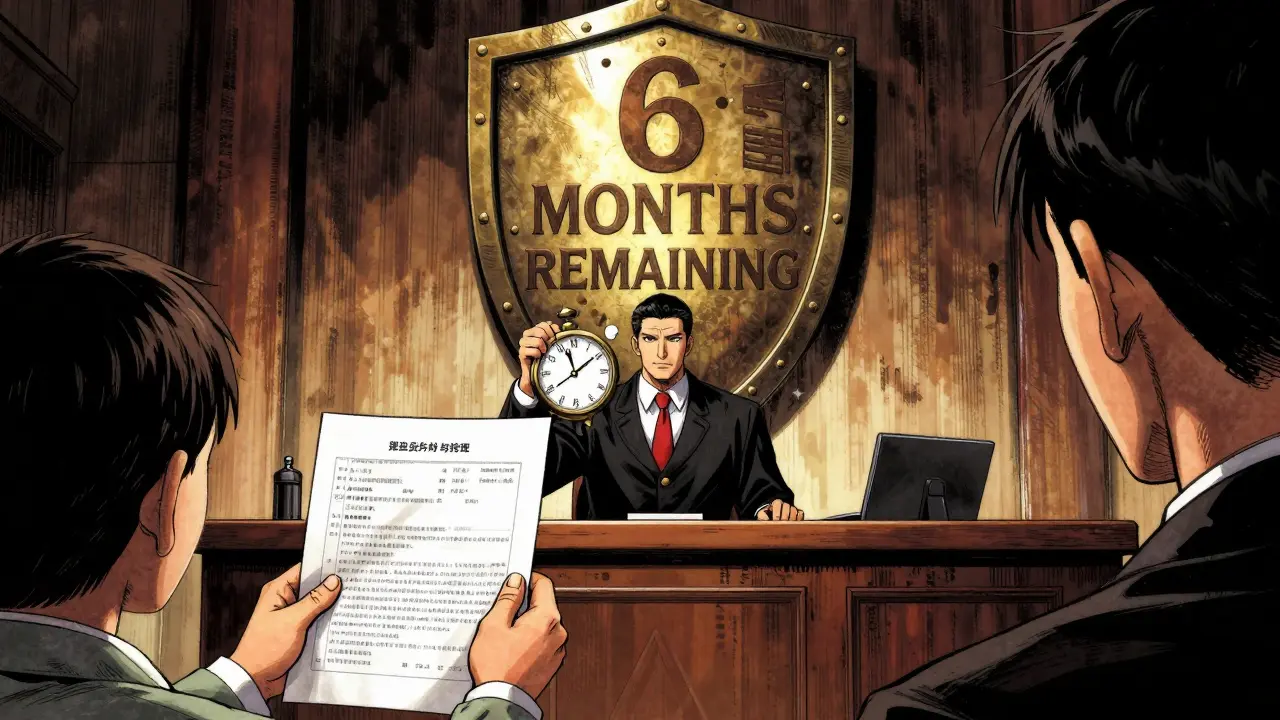

Most people think patent protection for drugs ends when the patent expires. But for many medications, the real clock on market exclusivity doesn’t stop there. In fact, the FDA can legally block generic versions from entering the market for six extra months - even after all patents have run out. This isn’t a patent extension. It’s something else entirely: pediatric exclusivity.

What pediatric exclusivity actually does

Pediatric exclusivity is a regulatory tool created under Section 505A of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. It doesn’t change the length of any patent. Instead, it gives the FDA a legal reason to delay approving generic drugs, even if those generics are perfectly legal under patent law. Think of it like a gate. The patent is one lock. Regulatory exclusivity is another. Pediatric exclusivity adds a third lock - one that only opens after six months, no matter what the patent says. This rule was designed to fix a real problem: drugs were being prescribed to kids all the time, but almost no studies had been done to prove they were safe or effective in children. So the FDA started offering a reward: if a drugmaker studies their medicine in kids and submits the results, they get six months of extra market protection. It’s not a bonus. It’s a trade.How it works in practice

It starts with a Written Request from the FDA. The agency tells the drug company: "We need you to test this drug in children for these conditions. Here’s what the study must include." The company then spends millions to run those studies. If they do it right - and submit the full report - the FDA reviews it within 180 days. If the studies meet the request, pediatric exclusivity is granted. Here’s the twist: the exclusivity doesn’t attach to the drug application. It attaches to the active ingredient. That means if a company makes a pill, a liquid, and a cream with the same active ingredient, and they study just one of them in kids, all three get the six-month extension. Same goes for every indication - cancer, ADHD, epilepsy - if the active moiety is covered, the exclusivity applies across the board. This is why pediatric exclusivity is so powerful. One study can protect an entire product line.It extends more than just patents

Pediatric exclusivity doesn’t just ride on top of patents. It stacks on top of other exclusivities too:- Five-year new chemical entity (NCE) exclusivity

- Three-year exclusivity for new clinical studies

- Orphan drug exclusivity

What happens after the patent expires?

This is where most people get confused. If a patent expires, and no other exclusivity remains, can a generic come in right away? No. Not if pediatric exclusivity is still active. The FDA treats pediatric exclusivity as a standalone barrier. Even if a generic applicant files a Paragraph II certification (meaning they say the patent is expired), the FDA still can’t approve the drug until the six-month exclusivity window closes. Courts have backed this up. In cases like Apotex’s challenge, the FDA’s position was upheld: pediatric exclusivity blocks approval regardless of patent status. That’s why some drugs sit on the market with zero patents left - but still no generics. The exclusivity is doing the heavy lifting.Who can’t use it?

Pediatric exclusivity only applies to small-molecule drugs. It doesn’t work for biologics. That’s because biologics are regulated under a different law - the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA). Under that law, patents don’t block FDA approval the same way. So even if a biologic maker runs pediatric studies, they get no extra market protection. This creates a big gap. A drugmaker with a small-molecule drug can lock out generics for six months after patent expiry. A biologic maker can’t. That’s why pediatric exclusivity is a prized tool for traditional pharma, but irrelevant for companies like Amgen or Genentech.How generics can still get in

There are only three ways a generic company can bypass pediatric exclusivity:- Get a waiver from the original drugmaker

- Win a court case proving the patent (or exclusivity) is invalid or not infringed

- Be sued for patent infringement - but the brand company doesn’t file suit within 45 days

Why it’s worth hundreds of millions

A blockbuster drug like Adderall or Prozac can make over $1 billion a year. Six months of exclusivity? That’s $500 million in extra revenue - just for running a few pediatric studies. That’s why companies invest heavily in this. Some even design their entire lifecycle strategy around it. They’ll delay filing a supplemental application until just before a patent expires - so the pediatric exclusivity kicks in right when the patent drops. It’s legal. It’s strategic. And it’s completely hidden from public view. You’ll never see it on the label. You won’t hear about it in ads. But it’s why your child’s medication still has no generic version - even if the patent expired years ago.Real-world example

Take the ADHD drug Vyvanse (lisdexamfetamine). Its main patent expired in 2023. But no generic has hit the market yet. Why? Because the manufacturer conducted pediatric studies under a Written Request from the FDA. The exclusivity granted in 2021 runs until mid-2026. Even though the patent is gone, the FDA can’t approve a generic until that clock runs out. That’s pediatric exclusivity in action. Not a patent. Not a trademark. Just a regulatory rule that gives a six-month head start - and it’s enforceable even without a patent.What this means for patients and payers

For patients, this delay means higher costs. For insurers and Medicaid, it means more spending on brand-name drugs. For generics, it means waiting - sometimes years - to enter the market. Critics argue this system rewards companies for doing what they should’ve done anyway: testing drugs on children. Supporters say it’s the only way to get companies to invest in pediatric research when there’s little profit in it. Either way, the system works. Since 1997, over 200 drugs have received pediatric exclusivity. Thousands of studies have been done. Pediatric labeling is now common. The goal was to protect kids. And it did. But it also created a powerful, quiet tool for drugmakers to extend profits - without ever touching a patent.Does pediatric exclusivity extend the actual patent term?

No. Pediatric exclusivity does not change the legal expiration date of any patent. It only delays the FDA’s ability to approve generic versions of the drug for six months, regardless of whether the patent is still active. This is a regulatory barrier, not a patent extension.

Can a drug get pediatric exclusivity if it has no patents left?

Yes - but only if the drug still has some form of regulatory exclusivity, like five-year NCE or three-year exclusivity, with at least nine months remaining. In rare cases, if a company submits a new pediatric indication for a drug with no exclusivity left, and that application requires new clinical studies, the FDA can grant pediatric exclusivity as part of the new approval.

Does pediatric exclusivity apply to biologics?

No. Pediatric exclusivity only applies to small-molecule drugs regulated under the Hatch-Waxman Act. Biologics are governed by a different law (BPCIA), and patents do not block FDA approval of biosimilars in the same way. So even if a biologic company studies its product in children, it receives no additional market protection.

How long does it take for the FDA to grant pediatric exclusivity after study submission?

The FDA has up to 180 days to review the pediatric study report after it’s submitted. If the studies meet the requirements of the original Written Request, the exclusivity is granted upon acceptance - not upon labeling approval. This means the clock can start before the pediatric label is finalized.

Can a generic company challenge pediatric exclusivity in court?

Yes - but only under limited conditions. A generic company can win approval if they prove in court that the patent covered by the exclusivity is invalid, not infringed, or unenforceable. They can also get approval if the brand company fails to sue within 45 days of receiving a Paragraph IV certification. Otherwise, the FDA must honor the exclusivity period.

Posts Comments

Selina Warren January 16, 2026 AT 15:52

This is pure corporate greed dressed up as public health. They get paid billions to test drugs on kids-something they should’ve done decades ago-and then they get rewarded with half a billion in extra profits? No. Just no. This isn’t incentivizing research; it’s blackmailing the system with children’s health as leverage. The FDA is complicit.

Robert Davis January 17, 2026 AT 16:11

Interesting. I didn’t realize pediatric exclusivity was a separate regulatory mechanism and not a patent tweak. I’ve always assumed it was just a loophole. Now I see it’s a whole parallel system. Still… kind of terrifying how opaque it is.

Jake Moore January 18, 2026 AT 08:36

Actually, this system has done more good than harm. Before 1997, 80% of pediatric prescriptions were off-label. Now? Most drugs have proper pediatric dosing and safety data. The six-month delay is a small price to pay for saving kids from dangerous, untested meds. Pharma’s profit isn’t the only metric here.

Joni O January 19, 2026 AT 18:14

So… if a drug has no patent left but still has pediatric exclusivity, generics literally can’t enter? That’s wild. I thought patents were the only thing blocking generics. This explains why my kid’s ADHD med is still $500 a month 😔

Max Sinclair January 20, 2026 AT 15:16

Thanks for breaking this down so clearly. I’ve seen headlines about ‘drug companies hiding behind patents’ but never realized regulatory exclusivity was the real gatekeeper. It’s not shady-it’s just buried in legalese. We need better public education on this.

Nishant Sonuley January 21, 2026 AT 02:33

Let’s be real-this whole system is a masterclass in corporate gaming. The FDA gives a six-month reward for doing what’s ethically mandatory, and pharma turns it into a multi-billion-dollar cash grab. Meanwhile, parents in rural towns can’t afford the brand version. The system isn’t broken-it was designed this way. And guess who designed it? Lobbyists with law degrees and private jets. 🤡

Emma ######### January 21, 2026 AT 05:56

I work in pediatric oncology. We’ve seen kids get better outcomes because of these studies. I get the outrage, but I’ve also seen what happens when we don’t have pediatric data. It’s not pretty. The system’s flawed, but the intent matters.

Andrew McLarren January 22, 2026 AT 06:51

It is imperative to note that the statutory framework governing pediatric exclusivity is codified under 21 U.S.C. § 355a, and its implementation is subject to rigorous administrative review. The mechanism does not constitute a patent extension, as elucidated in FDA guidance documents issued in 2002 and reaffirmed in 2018. Legal precedent, including Apotex v. FDA, affirms the agency’s authority to enforce such exclusivity irrespective of patent status.

Andrew Short January 23, 2026 AT 02:25

Of course the FDA lets them do this. They’re all in the pocket of Big Pharma. You think this is about kids? Nah. It’s about profits. Every single one of these ‘studies’ is just a shell game to delay generics. The real crime? The FDA approves these studies without ever requiring independent replication. It’s a rigged game, and you’re all too dumb to see it.

christian Espinola January 23, 2026 AT 03:12

They’re lying. This isn’t about kids. It’s about controlling the market. The FDA doesn’t even require the studies to show benefit-just that they were done. That’s why you see the same 30 kids in 5 different studies. They’re just checking a box. And the government lets them get away with it because they’re scared of lawsuits. This is how monopolies are built. Wake up.

Dayanara Villafuerte January 24, 2026 AT 19:55

So basically, pharma gets a free 6-month monopoly for doing the bare minimum? 😒 And we call this ‘public health policy’? I mean… 🤦♀️ I’m not mad, I’m just disappointed. Also, Vyvanse still costs more than my rent. #PharmaGreed

Danny Gray January 26, 2026 AT 05:53

Wait-so if a company delays submitting the pediatric study until right after the patent expires, they get six months of exclusivity *on top* of whatever else is left? That’s… actually genius. In a dystopian, capitalist, soul-crushing kind of way. It’s like they’re playing chess while the rest of us are still figuring out how pawns move. I hate that I respect it.

Wendy Claughton January 26, 2026 AT 06:25

This… this is so important. I didn’t know this existed. 🥺 I’ve been paying $400 for my daughter’s medication for years, thinking it was just ‘how things are.’ But now I know-it’s not natural. It’s engineered. And it’s not just about money-it’s about access. We need to fix this. 💔✊

Pat Dean January 27, 2026 AT 10:07

USA: where you can’t get a generic for your kid’s ADHD med because some corporation did the bare minimum and got rewarded with half a billion. Meanwhile, other countries have generics at 10% the price. This isn’t innovation. This is American capitalism at its most grotesque. We’re not #1-we’re #1 in corporate exploitation.

Write a comment