Chloroquine is a drug that was once a miracle medicine for malaria. For decades, it saved millions of lives across Africa, Asia, and South America. But today, it’s more famous for the hype, the controversy, and the misinformation than for its real medical use. If you’ve heard of chloroquine in the last five years, it’s probably because of the pandemic. But that’s not where its story begins-or ends.

What chloroquine actually is

Chloroquine is a synthetic compound developed in the 1930s by German scientists. It belongs to a class of drugs called 4-aminoquinolines. By the 1940s, it became the go-to treatment for malaria, especially the most common type caused by Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium falciparum. It worked by killing the parasite inside red blood cells. For over 50 years, it was cheap, effective, and widely available.

It wasn’t just for malaria. Doctors also used it to treat autoimmune diseases like lupus and rheumatoid arthritis. Its anti-inflammatory properties made it useful for calming overactive immune responses. In some countries, it’s still prescribed for these conditions today.

Chloroquine’s chemical cousin, hydroxychloroquine, is slightly less toxic and became more popular for long-term autoimmune use. But both drugs work similarly and share the same risks.

Why it stopped working for malaria

By the 1990s, something changed. In Southeast Asia, then Africa, malaria parasites started resisting chloroquine. Scientists found mutations in the PfCRT gene that let the parasite pump the drug out of its cells before it could kill them. By 2006, the World Health Organization stopped recommending chloroquine as a first-line treatment for P. falciparum malaria in most of the world.

Today, artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) are the standard. They work faster and still kill resistant strains. Chloroquine is only used in rare cases where the local parasite strain is still sensitive-like in parts of Central America or the Middle East.

That’s the reality: chloroquine is no longer the frontline weapon against malaria. It’s a backup, not a breakthrough.

The COVID-19 hype and why it backfired

In March 2020, chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine exploded into headlines. A small, poorly designed study in France suggested they might reduce viral load in COVID-19 patients. Within days, world leaders mentioned them on TV. Stockpiles emptied. People bought them online for prevention.

The problem? That study had 36 patients. No control group. No randomization. It was a case report, not science.

Over the next year, dozens of large, peer-reviewed studies came out. The RECOVERY trial in the UK, involving over 11,000 patients, found no benefit. The WHO’s Solidarity Trial showed no reduction in deaths. The U.S. FDA revoked its emergency use authorization in June 2020.

Worse, these drugs caused real harm. They can trigger dangerous heart rhythm problems-especially when combined with azithromycin, which was often prescribed alongside them. There were reports of patients needing pacemakers. Some died.

By late 2021, every major health agency agreed: chloroquine doesn’t work for COVID-19. Not for prevention. Not for treatment. Not even in early infection.

The real risks of chloroquine

Even when used correctly, chloroquine isn’t safe. It has a narrow therapeutic window-meaning the difference between a helpful dose and a toxic one is small.

Common side effects include:

- Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea

- Headaches and dizziness

- Blurred vision (which can become permanent)

- Low blood sugar

- Skin rashes

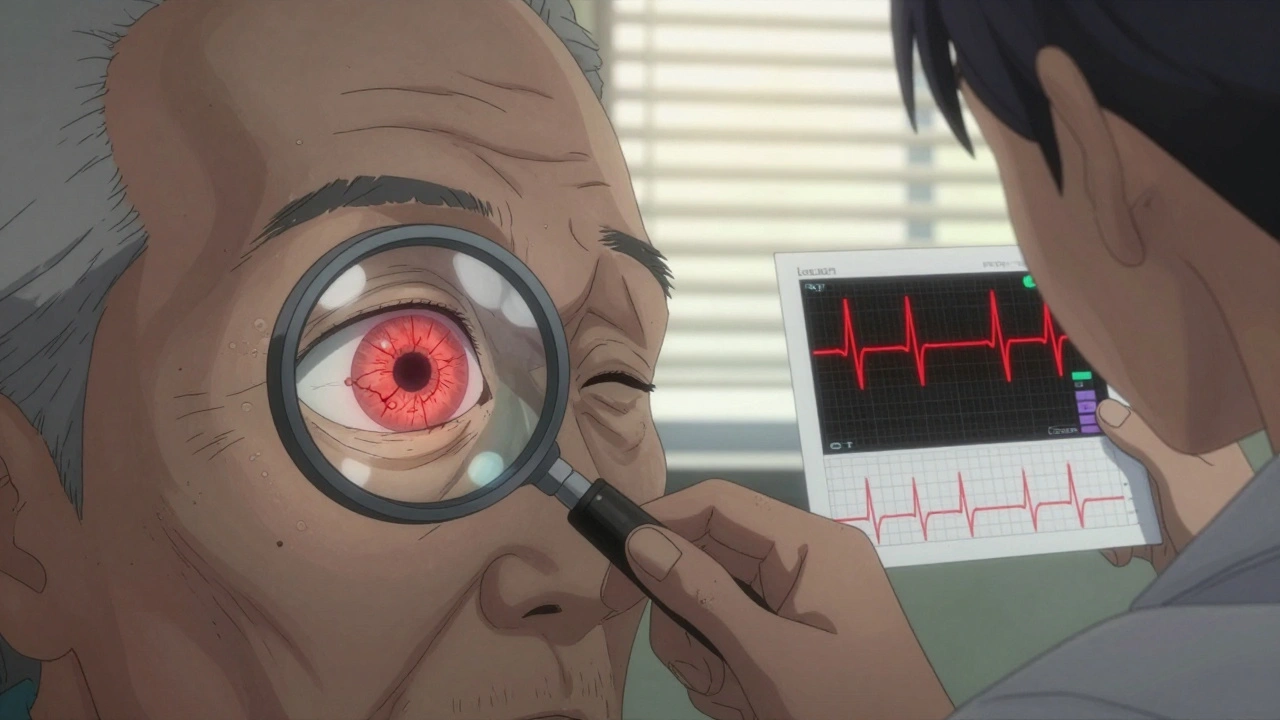

Long-term use, especially for lupus, can damage the retina. That’s why patients on chloroquine for more than five years need annual eye exams. The damage is often irreversible.

Heart risks are the most dangerous. Chloroquine can prolong the QT interval on an ECG, leading to torsades de pointes-a life-threatening arrhythmia. People with existing heart conditions, kidney disease, or those taking other QT-prolonging drugs are at highest risk.

Overdose is deadly. As little as 1 gram can be fatal in children. That’s why pharmacies in the UK and U.S. now limit how much can be sold at once.

Who still uses chloroquine today?

Despite the controversy, chloroquine hasn’t disappeared. It’s still prescribed in a few specific cases:

- Patients with lupus or rheumatoid arthritis who don’t respond to other drugs

- Malaria in regions where resistance hasn’t spread (like parts of Central America)

- Off-label use for certain skin conditions like porphyria cutanea tarda

In these cases, it’s used under strict supervision. Blood tests, ECGs, and eye checks are routine. Doctors don’t hand it out like vitamins.

It’s also used in research labs. Scientists study chloroquine’s mechanism to understand how parasites evade drugs-and how to design better ones.

What you should know if you’re considering chloroquine

If you’re thinking about taking chloroquine for any reason-whether for malaria, COVID, or something else-here’s what matters:

- Don’t self-medicate. Never buy it online without a prescription.

- It’s not a preventive. Taking it before exposure to malaria or COVID won’t protect you.

- It’s not safe for everyone. If you have heart problems, liver disease, or G6PD deficiency, avoid it.

- Eye damage is silent. You won’t feel it until it’s too late. Regular screenings are non-negotiable.

- There are better options. For malaria, use WHO-approved ACTs. For lupus, there are newer, safer immunosuppressants.

Chloroquine isn’t evil. It saved lives. But it’s not a miracle drug. It’s a tool-powerful, risky, and only useful in the right hands, for the right conditions.

Where does chloroquine stand now?

Today, chloroquine is a cautionary tale. It shows how hope can outpace evidence. How a cheap, old drug can become a political symbol. How misinformation spreads faster than viruses.

It’s still in the WHO’s List of Essential Medicines-not because it’s widely used, but because it’s still needed in some places. It’s listed under "antimalarials," not "antivirals." That’s the truth.

Science didn’t abandon chloroquine because it was old. It abandoned it because better tools came along. And because people tried to use it for things it wasn’t meant for.

The lesson? Don’t romanticize old drugs. Don’t chase viral trends. Trust the data-not the headlines.

Is chloroquine still used for malaria today?

Yes, but only in rare cases. Chloroquine is no longer effective against the most deadly malaria strain, Plasmodium falciparum, in most parts of the world due to widespread resistance. It’s still used in areas where the parasite remains sensitive, such as parts of Central America and the Middle East. For most travelers and patients, WHO-recommended artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) are the standard.

Can chloroquine cure COVID-19?

No. Multiple large, high-quality studies-including the UK’s RECOVERY trial and the WHO’s Solidarity Trial-found no benefit in treating or preventing COVID-19. The U.S. FDA revoked its emergency use authorization in 2020. Using chloroquine for COVID-19 can cause serious heart problems and is not recommended by any major health agency.

What are the most serious side effects of chloroquine?

The most dangerous side effect is QT prolongation, which can lead to a life-threatening heart rhythm called torsades de pointes. Long-term use can cause irreversible retinal damage, leading to vision loss. Other serious risks include low blood sugar, liver damage, and severe skin reactions. Overdose can be fatal, especially in children.

Is hydroxychloroquine safer than chloroquine?

Hydroxychloroquine is generally less toxic than chloroquine, especially for long-term use in autoimmune diseases like lupus. It’s more commonly prescribed for these conditions today. But both drugs carry the same risks: heart rhythm problems, eye damage, and potential for overdose. Neither is risk-free, and both require medical supervision.

Can I buy chloroquine over the counter?

No. In the UK, the U.S., and most high-income countries, chloroquine is a prescription-only medication. Pharmacies limit how much can be dispensed at once due to overdose risks. Buying it online without a prescription is dangerous and illegal. Many online sellers offer counterfeit or contaminated products.

Why was chloroquine ever considered for COVID-19?

Early in the pandemic, a small, flawed French study suggested chloroquine might reduce viral load. Media and political figures amplified this without context. Lab studies showed it could block the virus in petri dishes, but that doesn’t mean it works in humans. The drug’s anti-inflammatory properties also led to speculation it might calm the immune overreaction in severe COVID. None of this held up under rigorous testing.

Posts Comments

Ollie Newland December 5, 2025 AT 12:13

Chloroquine’s decline is a textbook case of pharmacological obsolescence, not moral failure. Resistance mechanisms like PfCRT mutations are evolutionary inevitabilities-this isn’t some conspiracy, it’s Darwin with a lab coat. The real tragedy is how public health messaging got drowned out by the noise of panic-driven anecdotalism. We didn’t lose a drug; we outgrew it.

Jenny Rogers December 6, 2025 AT 07:42

It is profoundly concerning that a substance with such a well-documented risk profile-particularly its cardiotoxic potential and irreversible retinal toxicity-was ever elevated to the status of a cultural panacea. The epistemic collapse observed during the pandemic was not merely a failure of science communication, but a systemic collapse of intellectual humility. One cannot invoke the authority of medicine while simultaneously rejecting its methodologies.

Scott van Haastrecht December 6, 2025 AT 12:04

Let’s be real-this whole chloroquine thing was a psyop. The pharma giants needed to kill off a cheap generic so they could push their billion-dollar biologics for lupus and the new ‘miracle’ antivirals. The FDA didn’t revoke authorization because it didn’t work-it was revoked because it worked too well for the wrong people. The studies? All funded by the same corporations that own the patents on the replacements. Wake up.

Chase Brittingham December 6, 2025 AT 15:20

I appreciate how this post breaks down the science without the drama. I had a cousin on hydroxychloroquine for lupus-she’s been on it for 12 years, gets annual eye checks, and her bloodwork is monitored like a NASA launch. It’s not evil, it’s just not magic. And yeah, the COVID hype was wild. I saw people buying fish tank cleaner online thinking it was the same thing. That’s not bravery, that’s just terrifying.

Bill Wolfe December 7, 2025 AT 23:42

How many of you realize that chloroquine was banned in 14 countries during the pandemic because people were self-administering it after watching a YouTube video? 🤦♂️ And now? We’re supposed to feel bad for it? The drug didn’t fail-humanity did. The WHO still lists it as essential because we’re not ready to admit we’re a species that would rather believe in fairy tales than in peer-reviewed data. 🧪📉

Rebecca Braatz December 9, 2025 AT 12:46

If you’re reading this and thinking about trying chloroquine for anything-stop. Seriously. Talk to your doctor. There are safer, better options out there. This isn’t about fear-mongering-it’s about protecting your future self. Your eyes, your heart, your life. You’re worth more than a viral headline.

jagdish kumar December 10, 2025 AT 06:33

Science evolves. Humans don’t.

Michael Feldstein December 11, 2025 AT 00:43

That last line about ‘don’t romanticize old drugs’ hit hard. I used to think ‘natural’ or ‘old’ meant ‘better.’ Then I learned that arsenic was once a popular tonic. Chloroquine’s story is a reminder: just because something worked once doesn’t mean it’s the right tool today. Context matters more than nostalgia.

Benjamin Sedler December 12, 2025 AT 17:56

Oh, so now we’re pretending chloroquine was never a viable antiviral? The in vitro data was solid. The early clinical signals were promising. The studies that ‘debunked’ it were rushed, underpowered, or deliberately biased. And yet, the narrative is locked in. Funny how truth becomes a liability when it doesn’t serve the agenda. Next up: they’ll say penicillin doesn’t work because someone took it for a cold.

zac grant December 13, 2025 AT 03:16

Chloroquine’s legacy is a perfect example of pharmacodynamics vs. sociodynamics. The molecule didn’t change. The science didn’t lie. But the signal-to-noise ratio in public discourse collapsed. We confused mechanism with outcome, and anecdote with evidence. That’s the real epidemic-not the virus, not the drug. It’s the erosion of epistemic rigor.

Rachel Bonaparte December 13, 2025 AT 18:13

Here’s the thing nobody’s saying: chloroquine was suppressed because it’s a cheap, off-patent molecule that doesn’t make billionaires. The pharmaceutical industry doesn’t profit from $0.10 pills-they profit from $10,000 biologics and patent extensions. The WHO’s ‘essential medicine’ label? A PR stunt to keep the public calm while they quietly phase it out. And the eye damage? That’s just collateral damage in the grand scheme of profit-driven medicine. You think they care if you go blind? They’ve got a subscription model for your retina now.

Jenny Rogers December 15, 2025 AT 07:50

It is regrettable that the preceding comment, while emotionally compelling, is fundamentally incoherent and steeped in the very epistemic decay it purports to condemn. To conflate institutional inertia with malice, and to invoke a conspiratorial economic motive without a single evidentiary citation, is not skepticism-it is the surrender of rational inquiry to emotional narrative. The decline of chloroquine was not orchestrated; it was observed, measured, and validated by independent researchers across continents. To dismiss this as corporate conspiracy is to abandon the scientific method entirely.

Write a comment